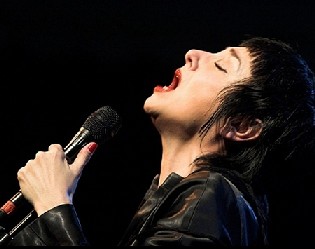

The musical genre called fado emerged, probably from Afro, Arabic, Brazilian and European sources, in the steep alleyways of the Mouraria and Alfama districts of Lisbon in the 19th century. During the 20th it became Portugal's national music.

The Hummel (i.e. bumblebee) is a simple zither-like string instrument with resonating drone strings,

which was widely-used until it fell out of favour in the 19th century such as other drone instruments

alike. In America only it evolved into the mountain dulcimer and got popular again thanks to the

folk revival [22].

Ulrich's book tells the story of the hummel, describes the style of playing and documents 44 historical

instruments with all detailled measurements. His main points are to prove that the hummel has its origins in Europe and

not in West Asia, as literature usually claims, and maybe trigger a renaissance for the instrument,

following on the heels of hurdy gurdy and pipes.

The Hummel (i.e. bumblebee) is a simple zither-like string instrument with resonating drone strings,

which was widely-used until it fell out of favour in the 19th century such as other drone instruments

alike. In America only it evolved into the mountain dulcimer and got popular again thanks to the

folk revival [22].

Ulrich's book tells the story of the hummel, describes the style of playing and documents 44 historical

instruments with all detailled measurements. His main points are to prove that the hummel has its origins in Europe and

not in West Asia, as literature usually claims, and maybe trigger a renaissance for the instrument,

following on the heels of hurdy gurdy and pipes.

Wilfried Ulrich, The Story of the Hummel.

Museumsdorf Cloppenburg,

2011, pp181, €22,00.

Pioneers of English Folk Guitar presents 10 classic songs from the folk revival era,

starting with Richard Thompson's [39]

motorcycle hymn "1952 Vincent Black Lightning".

Tuning is in CGDGBE, you have to learn to play with a thumb pick, and maintain a steady bass line.

Next is Davey Graham's [38]

instrumental "Anji", of which Ralph McTell once said: The hard part of this was that there were two

beats to every bass note instead of the one that most of us were able to play.

Furthermore, there are traditional songs - "Black Waterside" (Gordon Giltrap),

"Canadee-i-o" (Nic Jones),

"The Whale Catchers" (Martin Carthy) [45]

- as well as original music by John Renbourn, John Martyn,

Nick Drake (see left),

Jake Thackray and the late Bert Jansch [46].

The pieces were arranged in staff notes and tabs from the original recordings.

The lyrics are included as well as a (very short) artist biography.

Pioneers of English Folk Guitar presents 10 classic songs from the folk revival era,

starting with Richard Thompson's [39]

motorcycle hymn "1952 Vincent Black Lightning".

Tuning is in CGDGBE, you have to learn to play with a thumb pick, and maintain a steady bass line.

Next is Davey Graham's [38]

instrumental "Anji", of which Ralph McTell once said: The hard part of this was that there were two

beats to every bass note instead of the one that most of us were able to play.

Furthermore, there are traditional songs - "Black Waterside" (Gordon Giltrap),

"Canadee-i-o" (Nic Jones),

"The Whale Catchers" (Martin Carthy) [45]

- as well as original music by John Renbourn, John Martyn,

Nick Drake (see left),

Jake Thackray and the late Bert Jansch [46].

The pieces were arranged in staff notes and tabs from the original recordings.

The lyrics are included as well as a (very short) artist biography.

Adrian Hopkins (ed), Pioneers of English Folk Guitar - 10 Acoustic Guitar Songs from the Heroes of British Folk.

Wise Publications,

2011, ISBN 978-1-78038-199-2, pp72, €21,90.

Glaswegian Tom Richardson, who is the guitar player with the Phamie Gow Band [31]

and once played with Scottish group Brolum [20],

has published a second volume of self- composed tunes in the Celtic vein, probably suitable for any

melody instrument - not necessarily, even less so for the guitar.

63 tunes are featured in 5 chapters: 4/4 tunes such as the rollicking "Cowboy Ceilidh,"

the frenetic "Reel for Bartok" inspired by Bartok's piano pieces, or the

fluttering "Flight of the Butterfly". There is a

jig, "America," based on the Leonard Bernstein tune from "Westside Story,"

"Galloping Home" with changing time signatures between 9/8 and 12/8,

and some pipe tunes such as "Gordon and Fred", dedicated to his favourite pipers

Gordon Duncan [25]

and Fred Morrison [41].

The tunes are transcribed in standard notation, with guitar chords added.

Glaswegian Tom Richardson, who is the guitar player with the Phamie Gow Band [31]

and once played with Scottish group Brolum [20],

has published a second volume of self- composed tunes in the Celtic vein, probably suitable for any

melody instrument - not necessarily, even less so for the guitar.

63 tunes are featured in 5 chapters: 4/4 tunes such as the rollicking "Cowboy Ceilidh,"

the frenetic "Reel for Bartok" inspired by Bartok's piano pieces, or the

fluttering "Flight of the Butterfly". There is a

jig, "America," based on the Leonard Bernstein tune from "Westside Story,"

"Galloping Home" with changing time signatures between 9/8 and 12/8,

and some pipe tunes such as "Gordon and Fred", dedicated to his favourite pipers

Gordon Duncan [25]

and Fred Morrison [41].

The tunes are transcribed in standard notation, with guitar chords added.

Tom Richardson, Jigs, Reels and Fancy Feels Volume 2 - A Collection of 63 New and Exciting Tunes for Fiddle or Accordion.

Spartan Press,

2011, ISBN 979-0-57998-120-6, pp39, £11,50.

Andrew Gordon formerly wrote a tutorial for intermediate to advanced players.

This now is a small but exhaustive tutorial

to introduce beginners to rhythmic and solo guitar techniques for blues music, i.e.

teaching chracteristic riffs (short melodic or rhythmic phrases)

that make up blues guitar playing.

He introduces 100 such ideas in 5 sections to build up a vocabulary, namely

basic blues riffs, R&B, Boogie, Rock and Gospel influenced phrases.

Eventually, two blues songs are made up from some of the riffs,

a swing song and a straight one, to create an improvised blues solo to be used as a template.

Included is an audio CD featuring each example with the guitar part playing along with the rhythm section

as well as the rhythm section alone (piano, bass and drums) to play along with.

Also an optional MIDI file disk is available with further benefits such as changing tempi and keys.

Andrew Gordon formerly wrote a tutorial for intermediate to advanced players.

This now is a small but exhaustive tutorial

to introduce beginners to rhythmic and solo guitar techniques for blues music, i.e.

teaching chracteristic riffs (short melodic or rhythmic phrases)

that make up blues guitar playing.

He introduces 100 such ideas in 5 sections to build up a vocabulary, namely

basic blues riffs, R&B, Boogie, Rock and Gospel influenced phrases.

Eventually, two blues songs are made up from some of the riffs,

a swing song and a straight one, to create an improvised blues solo to be used as a template.

Included is an audio CD featuring each example with the guitar part playing along with the rhythm section

as well as the rhythm section alone (piano, bass and drums) to play along with.

Also an optional MIDI file disk is available with further benefits such as changing tempi and keys.

Andrew D. Gordon, 100 Ultimate Blues Riffs for Guitar.

A.D.G. Productions ADG145,

2011, ISBN 1-934163-40-6, pp66, US-$21.95 (incl. CD).

Forever Young! Bob Dylan got 70! Celebrations everywhere, e.g. on the D-Day Tribute

at Denmark's Tønder Festival [46].

Not one minute of these 2 hours was boring, his Œuvre is copious and varied enough.

This is also shown in these 100 hits from the early 1960s (Blowin' in the Wind) until the recent past

(Beyond Here Lies Nothin'), a compact package of melody line arrangements, complete lyrics and guitar chords.

The songs are arranged in successive chapters:

from "New Kid On The Block" in the Greenwich Village folk scene

to "Songs of Social Conscience", "Plugged In", "Back to Basics", ...

The hard-wearing PVC cover is made to carry it around for a long time and use it intensely -

at least until his Bobness' 100th birthday!

Forever Young! Bob Dylan got 70! Celebrations everywhere, e.g. on the D-Day Tribute

at Denmark's Tønder Festival [46].

Not one minute of these 2 hours was boring, his Œuvre is copious and varied enough.

This is also shown in these 100 hits from the early 1960s (Blowin' in the Wind) until the recent past

(Beyond Here Lies Nothin'), a compact package of melody line arrangements, complete lyrics and guitar chords.

The songs are arranged in successive chapters:

from "New Kid On The Block" in the Greenwich Village folk scene

to "Songs of Social Conscience", "Plugged In", "Back to Basics", ...

The hard-wearing PVC cover is made to carry it around for a long time and use it intensely -

at least until his Bobness' 100th birthday!

The Gig Book: Bob Dylan - Perfect for guitarists, keyboard players and all other musicians.

Wise Publications,

2010, ISBN 978-1-84938-071-3, pp304, €22.99.

Se eu soubesse que morrendo Tu me havias de chorar uma lágrima Por uma lágrima tua que alegria me dixaria matar If I thought that when I died, you would have to cry one tear For one of your tears how happy I would be to die

During the period of the Estado Novo 1933-1974, fado and folk music were appropriated by the Salazar regime. Hence a boom in rock and pop music during the 1980s, and fado was partly suffering from the negative image it had gained.

During the 1990s, novo fado was emerging and gaining popularity at home and abroad. Musicians were able to adapt the form to contemporary tastes and market it to a new audience. Wim Wenders's film "Lisbon Story" in 1994 was featuring the popular band Madredeus[26] with their musical mix of fado, chanson and psychedelic music.

Though veteran fadista Carlos Zel declared that fado can only be sung once has reached thirty years of age - at 30, we have finally experienced much happiness, sadness, life and death; we have witnessed births, burials, loved and been unloved in turn -, the new fado was centred on a group of mostly young singers from the post-revolutionary generation.

Many having practised other musical styles such as pop, rock or jazz: Joana Amendoeira,[45] Cristina Branco[41] (many songs set to music by guitarrista Custódio Castelo),[46] Katia Guerreiro,[22] Mariza,[38] Misia,[32] Ana Moura,[42] and Dulce Pontes[43] are at the forefront of a star system promoted by the contemporary world music network. (Note that the most successful fado artists these days are female, just as female guitarists are not to be expected.)

Only fado managed to become marketable as world music to non-Portuguese audiences, contrary to the light and uptempo pimba music, the dominant form of music in many village festivals, featuring electronic beats and keyboards mixed with rural textures such as the accordion or brass instruments.

One main lyrical theme is the city of Lisbon itself, celebrating the sights and sounds of the Portuguese capital, the alleyways, its inhabitants and the River Tejo. Furthermore, fado places a strong emphasis on the bedrock of hurt and loss, often referring to absent people.

Amor, ciúme, cinzas e lume, dor e pecado Tudo isto existe, tudo iste é triste, tudo isto é fado Love, jealousy, ashes and fire, sorrow and sin, All of this exists, all of this is sad, all of this is fado

There is the magical saudade, claimed by the Portuguese as a proudly cherished speciality. Rodney Gallop explains it as:

In a word saudade is yearning: yearning for something so indefinite as to be indefinable: an unrestrained indulgence in yearning. It is a blend of German Sehnsucht, French nostalgie, and something else besides. It couples the vague longing of the Celt for the unattainable with a Latin sense of reality which induces realization that it is indeed unattainable, and with the resultant discouragement and resignation.

There has been not that much written in English about fado. Richard Elliott's scholarly work in the Ashgate Popular and Folk Music Series[36][40] which previously published Vernon's "History of the Portuguese Fado" in the late 1990s, presents his research carried out on fado music and explores and discusses the above mentioned issues - origins, categorization, place, paths and trajectories.

Elliott puts a focus on new fado on one hand, and on the other on Amália Rodrigues (1920-1999),[46] the single most paradigmatic performer in modern Portuguese musical culture (Elliott) and the paradigm, the hinge and the epicentre of fado (Manuel Halpern).

Fado and the Place of Longing is essentially an academic textbook. For the general reader it is most interesting when Elliott gives specific examples from his comprehensive research. By and by,the book becomes a start for the uninitiated to explore the fado music of the last two decades and world music's crossover and fusion projects. His account ends with Lisbon's Deolinda,[43] who are fado despite playing music you can dance to and dressing in lively, happy, colourful clothes, and the suburban OqueStrada,[43] who is not fado but celebrates fado and its fadistas.

The Portuguese claim that saudade is an emotion only Portuguese people may feel, and the word is not translatable into the English language. The concept, however, is not alien to Englishmen, as Nick Cave proves (cited by Richard Elliott):

As Nick Cave did, Nick Drake probably also understood the meaning of saudade. The English singer/songwriter had been born in 1948. He started playing guitar listening to Dylan, Renbourn and Jansch. By the age of 18 he had a repertoire of standard folk songs and some of his own fragile, melancholy yet never self-indulgent musical confessions.

In 1969, Drake supported Fairport Convention at the Royal Festival Hall. Fairport bassist Ashley Hutchings reported to producer Joe Boyd who got impressed by the melodically unusual and sophisticated songs. Drake subsequently signed to Island Records. However, he did no more than a dozen gigs and recorded only 31 songs on three albums in four years. Upon completion of 1972's "Pink Moon", he withdrew to his parents' home in rural Warwickshire, where he died from an overdose of antidepressants in 1974. He was 26 years old.

Richard Thompson once wondered: People say that I'm quiet, but Nick's ridiculous. He's extremely talented, and if he wanted to be, he could be very successful. John Martyn explains:

He never felt comfortable in front of an audience. He just didn't like going on and playing. He primarily played for his own amusement. In those days 'Purple Haze' was in, and here he was singing all these gentle, breezing little ballads, and I can just imagine them swigging back the Carlsberg Special and totally giving him an awful hard time.

Since critics were indifferent and the record-buying public didn't care, his death passed largely unnoticed. However, it is not true that he only sold six copies because there are only that many people miserable enough to buy it. Drake's work has gradually inspired a small following, he has become a cult, his records revered, his life a subject of endless scrutiny and speculation. His record company always trusted that

Nick Drake is a great talent. His first two albums haven't sold a shit, but if we carry on releasing them, maybe a lot more people will get to hear Nick Drake's incredible songs and guitar playing. And maybe then they'll buy a lot of records and fulfil our faith in Nick's promise.

They did their job (and sure nobody in the music biz today takes such chances). Nick Drake is still available on CD. A biography has been written, tribute concerts held, his songs recorded, e.g. U.S. pop band Freak Owls only recently did a cover of Nick’s "Place to Be".[45] His music has been used in the film "Practical Magic", and Volkswagen used "Pink Moon" in a TV commercial. Within a month Drake had sold more records than he had in the previous 30 years.

Between 1994 and 2000 Jason Creed published 19 issues of the "Pink Moon" fanzine, devoted to the life and work of Nick Drake, featuring a collection of articles, interviews, reviews with some additional commentary. Maybe 200 pages of The Pink Moon Files is a bit too much about a man whose personal life is hardly known, so there is a lot of repetition here. It is rather meant for die-hard fans, and can only be an addition to the existing biography of Patrick Humphries or Peter Hogan's "Complete Guide to His Music".

I found most interesting the section on Drake's guitar technique, employing strange and complicated tunings. The late American guitar player Scott Appel did an analysis:

One of the most baffling, unconventional guitarists to emerge from his era.

His first influences were his contemporaries: Bert Jansch, John Renbourn and,

most importantly, John Martyn. His first focus, like those mentioned,was

traditional blues, but he quickly began to transcend the form and its limitations.

Within two years of having first picked up a guitar, he was composing his own

songs. His earliest compositions were simple, plaintive songs in standard

tuning. He would soon dismiss them as amateurish, and utilised conventional

tunings rarely from that point on.

'Place to Be' is a good place to start. The basic changes are simply D E - F#m.

Gradually, the tuning he employed became D A D G A F#, a D Major tuning with a

suspended fourth. Actually all of the tunings he utilised were suspensions of

some sort (stemming from D Modal), where he could use the odd voice as a passing

tone or add it to a minor block creating a four or five voiced minor seven or nine.

Elsewhere, he would tune the sixth string up a full step-and-a-half, to a G,

as on 'Fly' (D A D G D G capo 1). On 'Hanging on a Star' he would tune the

sixth string down to a C, four ledger lines below the staff: C G C F C E.

Nevertheless, it is good to spread the gospel. When Jason Creed first was visiting Nick's hometown in 1993 and was snooping around, he was stopped by the village constabulary. It turned out they'd never heard of Nick Drake. You did now! And though I've heard the name Nick Drake many a time, I can't recall having heard a song in my life. I'll do now!

England's neighbour Wales is often called the Land of Song.[39] Jazz clarinetist Wyn Lodwick recalls that American jazzmen once said to him, we know a lot of guys from England and Europe who play very well, but they don't swing. You guys from Wales you swing! Is it in the blood? Fiddler Angharad Jenkins (Calan), daughter of harpist Delyth Jenkins,[33] remembers

first hearing music live when Mum was playing in Aberjabber, and they used to come over to practice. But Mum reckons that I was the bump that she used to rest the harp on, so I was getting the vibrations direct even before I was born!

Aberystwyth resident Bruce Cardwell, who plays flute, pipes and a number of other instruments, envisions the birth of music at the dawn of time:

I have a quite definite and distinct vision, one that originated while living in the West of Ireland in 1977. The dogs became affected by the moon, and started to howl, their voices coming in and out, refrains and counter-melodies, harmonies almost. This was a performance, a social event, a ceremony. I lay listening to, half asleep, and had a picture of a group of hunter-gatherers round a fire one night, thousands of years before, hearing a similar sound and thinking, Why don't we try something like that...?

The sound of the voice is followed by manufacturing musical instruments, and, though living in the 21st century, he places an emphasis on acoustic instruments.

I recall being half amused and half irritated on being told that I was wasting my time

learning to play all those different instruments - a keyboard synthesiser which could

produce all of those sounds at the touch of a button. At that time it was my opinion

that acoustic instruments produced an infinitely varied series of notes, depending on

which other note came before, marginal inconsistencies in manual technique, environmental

elements like temperature or humidity, and the ability of the player.

An acoustic note is an inconsistent vibration, unlike an electronically generated impulse.

There seem to be issues involved for musicians regarding identity, and legitimacy, in

selecting to play acoustic instruments. They have a presence, and an ambience, which does

not emanate in the same way from the electrical imitators. There is a connection involved

in playing an instrument which developed in the music, and for the music, which links the

player in a time-honoured bond with material.

Whatever about the relevant values and motivations, the fact remains that in spite of the

economic dominance of commercial marketing a great many people are deeply involved in

playing and appreciating less mainstream music.

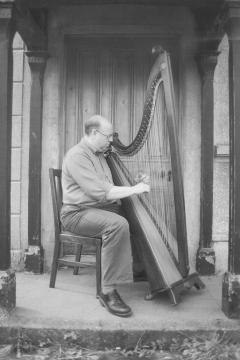

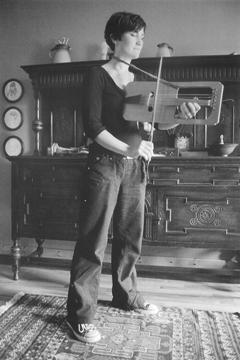

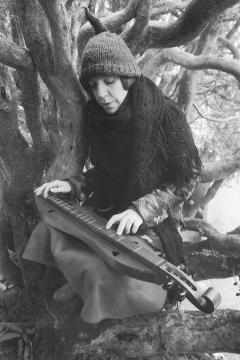

Reason enough for his book Noteworthy: Images of Welsh Music, depicting part of the acoustic music scene in Wales. It is essentially a collection of splendid black & white photographs, the musicians shot in their natural habitat while playing. Cardwell was trying for images with life in them, even at the expense of ultimate technical perfection, and thus using no flashlights at all.

There is Welsh Music from A as brass band Aberystwyth Silver Band to W as clarinetist Wyn Lodwick. There's amateurs, and there's the professionals, such as singer/piper partners Julie Murphy and Ceri Rhys Matthews (Fernhill),[33] or harpist Robin Huw Bowen.[35] Besides the natives, there's the recent arrivals. Cass Meurig, who played with Pigyn Clust and Fernhill, hails actually from North Yorkshire, though she is now strongly identified with Welsh culture by playing the crwth, a 12th century predecessor of the fiddle.[41]

Some are more exotic and come from further afield, such as Selim Sheikh, a central figure in the Indian music scene in Wales, or Hubert Placide from Saint Lucia in the West Indies. It turns out that Wales is not always the tolerant Land of Song as the cliché suggests:

I grew up listening to music. In Saint Lucia music is just part of the community. Everybody plays, and very loud! I would wake up hearing music from three hundred yards away, at five o'clock in the morning ... nobody ever complains. I have had letters here in Cardiff, though, about too much music coming from my house. I call Cardiff the retirement home for musicians, because the music scene is quieter here!

The photographs are accompanied by interviews, Bruce questioning the artists, how they became involved with music, what does it mean to them, and what drew them to Wales. It's nice to browse through this beautiful book, and it is a fine introduction to the rich and varied Welsh music scene, since the Land of Song is still a blank area for most people beyond Offa's Dyke.

Let's finish off with Stephen Rees (Ar Log,[35] Crasdant[35]), at the time being artistic director of the traditional Welsh music orchestra Glerorfa, who provides the adequate closing words here:

I wanted to instil a sense of pride in the Welsh repertoire, as an equal of that from any of the other Celtic countries, and to foster a joy in the performing of it. Welsh music at the moment provides great scope for creativity, because it is not hidebound by a prescriptive weight of precedence or tradition.

Photo Credits:

(1ff) Book Covers (from website/author/publishers);

(9) Nick Drake,

(10) Misia (unknown);

(11) Robin Huw Bowen,

(12) Cass Meurig,

(13) Sharron Kraus

(by Bruce Cardwell).