FolkWorld Article by

Walkin' T:-)M:

The Return of the Strathspey King

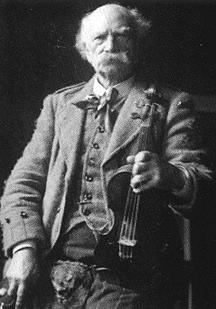

James Scott Skinner (1843-1927)

James Scott Skinner (1843-1927), the self-styled

Strathspey King, was the leading performer of Scottish

fiddle music in his day. His name lives on, many of his

compositions are still popular. But Skinner also recorded himself,

both on cylinder and early vinyl discs, which has been only recently

re-issued as `James Scott Skinner: The Strathspey King'

(Temple COMD2084 -> FW#24).

James Skinner was born on 5th August 1843 in Banchory,

a village 20 miles from Aberdeen, the youngest son of William Skinner and Mary

Agnew. His father died when James was only eighteen months old.  He originally was a gardener who also played the fiddle, but he lost three fingers

when the flint-lock pistol he was firing, as was a wedding custom, burst. Unable

to make a living from gardening, William became a left-handed fiddler and a

dancing master. James's older brother Alexander (Sandy) began teaching him fiddle

and cello when he was six. Sandy was the most rigorous of taskmasters,

and passed out humiliating punishment whenever he was slow.

He originally was a gardener who also played the fiddle, but he lost three fingers

when the flint-lock pistol he was firing, as was a wedding custom, burst. Unable

to make a living from gardening, William became a left-handed fiddler and a

dancing master. James's older brother Alexander (Sandy) began teaching him fiddle

and cello when he was six. Sandy was the most rigorous of taskmasters,

and passed out humiliating punishment whenever he was slow.

`With a view to assisting Sandy at dances, I also received

simple instruction in the art of vamping on the cello, which in those days

was called the bass fiddle, and was transported from place to place

in a green baize bag.'

Soon afterwards James came under the patronage of fiddler

Peter Milne

(1824-1908), the `Tarland Minstrel'. Practically a father to me,

Milne became an opium addict after taking it as a cure for rheumatism:

I'm that fond o' my fiddle, I could sit in the inside o't, an' look oot.

Milne and Skinner performed at dances around Deeside. It was nothing unusual for

Peter and me to trudge eight or ten weary miles on a slushy wet night in order

to fulfill a barn engagement.

`I remember getting back from such a tramp about five o'clock in

the morning. So tired was I that when I got to the door, dragging, rather

than carrying, my bass fiddle, I had neither the strength nor the will power

to lift the latch and enter. I must have been in a subconcious state, for

when my mother opened the door about seven I fell right through the doorway,

and lay helpless at her feet. I had been sleeping against the door, in a

half-standing, half-leaning posture for two hours at least.'

In 1855, James joined `Dr Mark's Little Men,' a touring show of orphan  boys who performed light classical music. While in the orchestra, based in Manchester,

James studied with violinist Charles Rougier and learned to read music. The

orchestra performed before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace and was busking

for money in the streets at the same time. Skinner returned to Aberdeen in 1861

and trained to be a dancing master with `Professor' William Scott. He adopted

his instructor's surname and eventually worked as a dancing teacher. The following

year he won several prizes for dancing and played at a fiddle competition in

Inverness gaining the first prize. The Queen requested him to teach the tenants

at Balmoral Castle.

boys who performed light classical music. While in the orchestra, based in Manchester,

James studied with violinist Charles Rougier and learned to read music. The

orchestra performed before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace and was busking

for money in the streets at the same time. Skinner returned to Aberdeen in 1861

and trained to be a dancing master with `Professor' William Scott. He adopted

his instructor's surname and eventually worked as a dancing teacher. The following

year he won several prizes for dancing and played at a fiddle competition in

Inverness gaining the first prize. The Queen requested him to teach the tenants

at Balmoral Castle.

He married fellow-dancer Jane Stuart of Aberlour, with whom he had a

daughter and a son. After a brief interlude as a blackface minstrel,

James Scott Skinner began his career as concert violinist in earnest.

`I had the patronage of all the big private families in

Ross-shire, Inverness-shire, Elginshire and Banffshire. I was making about

£750 a year, and was able to drive to and from the residences of my pupils

in my own private trap, drawn by a beautiful pony. This equipment cost me

about £150.'

Skinner ended up playing to vast audiences at London's Palladium and Royal

Albert Hall, usually dressed in kilt: The very embodiment

of the romantic Victorian version of traditional Highland culture, largely a

retrospective invention of the later 18th and early 19th centuries.

The kilt itself, for example, was invented about 1730 by

Thomas Rawlinson,

a Quaker industrialist from Lancashire. (P. Cooper)

`The triumph of the evening was left to Mr Scott Skinner,

who treated the audience to a brilliant display on the violin. The

appreciation of the audience reached its climax when the veteran danced a

step or two to his own strathspeys and reels.'

However, he was struck by personal tragedies. The crash came suddenly,

and in a single day I was roofless, wifeless, and penniless.  His wife Jane was committed to Elgin Lunatic Asylum suffering from excitement

caused by pecuniary embarrassment, where she died a pauper. Skinner married

Gertrude Park, but she resigned and went to Rhodesia, stripping their

cottage of everything, even the bed clothes. Perhaps it was his own arrogance.

Skinner adopted the title `The Strathspey King', using it to sign his letters.

Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must, says another of his

slogans. He quoted the alleged opinion of Vittorio

Monti (1868-1922), an Italian expert:

His wife Jane was committed to Elgin Lunatic Asylum suffering from excitement

caused by pecuniary embarrassment, where she died a pauper. Skinner married

Gertrude Park, but she resigned and went to Rhodesia, stripping their

cottage of everything, even the bed clothes. Perhaps it was his own arrogance.

Skinner adopted the title `The Strathspey King', using it to sign his letters.

Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must, says another of his

slogans. He quoted the alleged opinion of Vittorio

Monti (1868-1922), an Italian expert:

`Monti was a great admirer of my work. On one occasion he

picked up a couple of books and remarked, Here's Bach and here's Scott

Skinner. Personally I prefer Scott Skinner.'

Skinner once remarked: I have no intention of wearying my readers with

the details of my life's output of original music, which, frankly speaking, has

been colossal. And he was right. His repertoire combined the music

of the Scottish violin composers as the

Gows,

William Marshall,

etc. with over 600 compositions of his own. Skinner felt that

`the great work of my life has been composing music for the

people of Scotland. The music that reaches and lives in the hearts of

the people is the music that they whistle or sing at their daily toil or in

their hours of recreation, that the mother croons o'er the cradle, and that

accompanies her children, a joyous companion, through life.'

He was desperate to publish his gargantuan output of tunes. Any profits went

immediately into tune collections. Skinner also published `A Guide to Bowing' and he

was able to make recordings on early wax cylinders and on 78 rpm discs,

partly done with a

Stroh fiddle

to increase the volume.

An Aberdonian, resident in Los Angeles, wrote to him: This is the first

real music I have heard in all those years. I have played this record over

the telephone to all my Scotch friends and to more fully enjoy these fine

Highland tunes I dress up in my kilt for the occasion.

Just a few examples (which can be heard on

`James Scott Skinner: The Strathspey King' ->

FW#24):

The `Laird o' Drumblair' (strathspey ->

FW#22) and the

`Iron Man' (strathspey ->

FW#22)

are dedicated to Skinner's friend and patron William M.F. McHardy of Drumblair.

The engineering entrepreneur gave Skinner the use of a rent-free cottage.

It's a classic Scots strathspey in the bright-sounding key of A with all

the hallmarks of Scottish style - snap rhythms, alternating (double tonic)

phrases in A-major and B-minor and ingenious descending runs of triplets

at the end. (Cooper) Skinner was in bed reflecting on all the

kindnesses of this friend: Suddenly a tune, `pat' and complete,

flashed into my head in his honour. I jumped out of bed,

but a search produced nothing better than a piece of

soap paper, and on this I promptly dashed off `The Laird o' Drumblair.' And

the tune was dispatched as it had been written.

His wife protested: Ye're no' gaun tae send that awfy-like paper tae the

Laird. He'll jist licht his pipe wi' it! But McHardy was so impressed

that he sent a cheque every following Christmas.

`Gavin M'Millan' (reel ->

FW#2)

was Skinner's agent round Glasgow;

`Gladstone' (reel ->

FW#14,

FW#20,

FW#24)

an Edinburgh music lover;

the `Laird o' Thrums' (strathspey ->

FW#2)

James M. Barrie

(1860-1937, author of `Peter Pan');

the `Left Handed Fiddler' (reel ->

FW#10,

FW#12,

a Donegal version is known as `Columba Ward's' ->

FW#14)

George Taylor of Aberdeen.

The `Cameron Highlanders' (pipe march ->

FW#16)

is titled after the Highland regiment in which Skinner's brother Sandy served.

The `Spinning Wheel' (reel ->

FW#2) and the

`Auld Wheel' (reel ->

FW#11)

refer to the mill at Hirn near Skinner's native Banchory.

(Irish fiddler

John Doherty

titled the sequence of both reels and Skinner's "Bride's Reel,"

-> FW#2,

`Flood on the Holm,'

-> FW#2,

FW#3).

Skinner vividly remembered James Johnston, the

`Miller o' Hirn' (strathspey ->

FW#22),

where he found dancing fiddle strings and warm friendships.

Confident that his tune would replace the famous `Miller o' Drone'

(-> FW#18),

Skinner boasted:

We'll Drone nae mair, sin' we ha'e got

The Miller o' the Hirn, O.

He was wrong anyway. The following verse was sung to the tune:

Lad, cam' ye doun by Feugh's green howe,

The Feugh that rins through Crathes, O?

Heard ye a fiddler dirl a bow,

Wi' something like a pathos, O?

Weel, gin he meet wi' your applause,

I brawly can discern, O,

The dusty-noted fiddler was

`The Miller o' the Hirn,' O.

The `Bonnie Lass o' Bon Accord' was written in December 1884 in Aberdeen.

It's inspirer was a young girl named Wilhelmina Bell whose father used to

play bass fiddle for my father. She was a splendid dancer, but was having to

work as a servant, for her father had been ruined by taking on a friend's

debts. `Never mind, my lassie,' said I, cheerfully. `I'll ma' a tune that'll

maybe keep ye in min' when we're baith deid.' Skinner wrote the tune the

following morning, and photographer Alexander Dinnie suggested to

make it something about Bon-Accord, the city's motto.

James Scott Skinner died on 17 March 1927. The Aberdeen

City Police Pipe Band led the funeral procession to Allenvale Cemetery,

as many as 40,000 people lining the streets, and piper George S. MacLennan played

`Lochaber No More' over the grave. A bronze bust was unveiled by his friend

Sir Harry Lauder (1870-1950) in

1931, the opening bars of `The Bonnie Lass o' Bon Accord' inscribed on the stone.

Sir Harry Lauder (1870-1950) in

1931, the opening bars of `The Bonnie Lass o' Bon Accord' inscribed on the stone.

A memorial plaque to Skinner can also be found on the High Street

in Banchory. Here, the

Banchory Strathspey and Reel Society

was formed in 1932:

`If I ever needed to calibrate a metronome, I shall simply switch

on when the Banchory Strathspey and Reel Society are in concert. Such is the

precision, the consistency and purity of their music. With James Scott

Skinner looking down and listening to their every note, they have much to

live up to. I'll bet the Strathspey King himself would be proud that his

legacy is in such brilliant hands. The swing, the lilt, the emotion and the

sheer breathtaking flamboyance of the music flows from their fiddles like

water of a clear, crystal fountain.' (M. Mulford)

Skinner and his classically trained contemporaries virtually changed the

face of Scottish music. Though some are reluctant,

Dick Gaughan

(-> FW#9,

FW#23)

once said those tunes were composed with the aid of a slide-rule.

Others disregard the reflection of a romanticised sentimentality,

detracting from the essence of Scottish music.

But Scottish musicians today are generally fond of Skinner's tunes

(e.g. -> FW#2,

FW#2,

FW#12,

FW#14,

FW#22),

and Bruce MacGregor

(-> FW#14,

FW#15,

FW#20,

FW#23,

FW#23,

FW#23)

states it clearly:

`Whatever the claims against Skinner's music, the one

thing that is patently clear, is that he cannot be ignored. Skinner had an

ear for a melody that encapsulated the emotions of his fellow Scots.

We'll never truly know what went on in Skinner's mind, or

fully understand what drove him on; in many respects it doesn't really matter.

What is clear is that his music possesses the unique elements of Scottish

music; passion, vigour, heart and soul and as long as those are the core

elements of traditional music, then James Scott Skinner will always remain

The King.'

James Scott Skinner `The Strathspey King';

Temple Records;

COMD2084; 2002. (-> FW#24)

Links:

www.mustrad.org.uk

www.folkicons.co.uk

www.nefa.net

www.scottish-fiddle.com

users.argonet.co.uk/fiddlers/

www.angus.gov.uk

www.wallacemusic.co.uk

www.hardiepress.co.uk

www.geocities.com/hamo_2000/

users.argonet.co.uk/tunes/

Back to the content of FolkWorld Features

To the content of FolkWorld No. 25

© The Mollis - Editors

of FolkWorld; Published 5/2003

All material published in FolkWorld is © The

Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews

and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source

and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors

for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest

care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content

of the linked external websites.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The

Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

He originally was a gardener who also played the fiddle, but he lost three fingers

when the flint-lock pistol he was firing, as was a wedding custom, burst. Unable

to make a living from gardening, William became a left-handed fiddler and a

dancing master. James's older brother Alexander (Sandy) began teaching him fiddle

and cello when he was six. Sandy was the most rigorous of taskmasters,

and passed out humiliating punishment whenever he was slow.

He originally was a gardener who also played the fiddle, but he lost three fingers

when the flint-lock pistol he was firing, as was a wedding custom, burst. Unable

to make a living from gardening, William became a left-handed fiddler and a

dancing master. James's older brother Alexander (Sandy) began teaching him fiddle

and cello when he was six. Sandy was the most rigorous of taskmasters,

and passed out humiliating punishment whenever he was slow.

boys who performed light classical music. While in the orchestra, based in Manchester,

James studied with violinist Charles Rougier and learned to read music. The

orchestra performed before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace and was busking

for money in the streets at the same time. Skinner returned to Aberdeen in 1861

and trained to be a dancing master with `Professor' William Scott. He adopted

his instructor's surname and eventually worked as a dancing teacher. The following

year he won several prizes for dancing and played at a fiddle competition in

Inverness gaining the first prize. The Queen requested him to teach the tenants

at Balmoral Castle.

boys who performed light classical music. While in the orchestra, based in Manchester,

James studied with violinist Charles Rougier and learned to read music. The

orchestra performed before Queen Victoria at Buckingham Palace and was busking

for money in the streets at the same time. Skinner returned to Aberdeen in 1861

and trained to be a dancing master with `Professor' William Scott. He adopted

his instructor's surname and eventually worked as a dancing teacher. The following

year he won several prizes for dancing and played at a fiddle competition in

Inverness gaining the first prize. The Queen requested him to teach the tenants

at Balmoral Castle.

His wife Jane was committed to Elgin Lunatic Asylum suffering from excitement

caused by pecuniary embarrassment, where she died a pauper. Skinner married

Gertrude Park, but she resigned and went to Rhodesia, stripping their

cottage of everything, even the bed clothes. Perhaps it was his own arrogance.

Skinner adopted the title `The Strathspey King', using it to sign his letters.

Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must, says another of his

slogans. He quoted the alleged opinion of

His wife Jane was committed to Elgin Lunatic Asylum suffering from excitement

caused by pecuniary embarrassment, where she died a pauper. Skinner married

Gertrude Park, but she resigned and went to Rhodesia, stripping their

cottage of everything, even the bed clothes. Perhaps it was his own arrogance.

Skinner adopted the title `The Strathspey King', using it to sign his letters.

Talent does what it can, Genius does what it must, says another of his

slogans. He quoted the alleged opinion of