Like all other travelling musicians, German group Cara had been grounded due to the pandemic.[76] Thus, the four troubadours used the forced break to study again The English and Scottish Popular Ballads anthologized by Francis James Child during the second half of the 19th century. Here are the stories of True Thomas the Rhymer and The False Lover.

Sir Thomas de Ercildoun, better remembered as Thomas the Rhymer (fl. c. 1220 – 1298, also known as Thomas Learmont or True Thomas, was a Scottish laird and reputed prophet from Earlston (then called "Erceldoune") in the Borders. Thomas' gift of prophecy is linked to his poetic ability. He is often cited as the author of the English Sir Tristrem, a version of the Tristram legend, and some lines in Robert Mannyng's Chronicle may be the source of this association. It is not clear if the name Rhymer was his actual surname or merely a sobriquet.

In literature, he appears as the protagonist in the tale about Thomas the Rhymer carried off by the "Queen of Elfland" and returned having gained the gift of prophecy, as well as the inability to tell a lie. The tale survives in a medieval verse romance in five manuscripts, as well as in the popular ballad "Thomas Rhymer" (Child Ballad number 37). The romance occurs as "Thomas off Ersseldoune" in the Lincoln Thornton Manuscript.

The original romance (from c. 1400) was probably condensed into ballad form (c. 1700), though there are dissenting views on this. Walter Scott expanded the ballad into three parts, adding a sequel which incorporated the prophecies ascribed to Thomas, and an epilogue where Thomas is summoned back to Elfland after the appearance of a sign, in the form of the milk-white hart and hind. Numerous prose retellings of the tale of Thomas the Rhymer have been undertaken, and included in fairy tale or folk-tale anthologies; these often incorporate the return to Fairyland episode that Scott reported to have learned from local legend.

Sir Thomas was born in Erceldoune (also spelled Ercildoune – presently Earlston), Berwickshire, sometime in the 13th century, and has a reputation as the author of many prophetic verses. Little is known for certain of his life but two charters from 1260–80 and 1294 mention him, the latter referring to "Thomas de Ercildounson son and heir of Thome Rymour de Ercildoun".

Thomas became known as "True Thomas", supposedly because he could not tell a lie. Popular lore recounts how he prophesied many great events in Scottish history, including the death of Alexander III of Scotland.

Popular esteem of Thomas lived on for centuries after his death, and especially in Scotland, overtook the reputation of all rival prophets including Merlin, whom the 16th century pamphleteer of The Complaynt of Scotland denounced as the author of the prophecy (unity under one king) which the English used as justification for aggression against his countrymen. It became common for fabricated prophecies (or reworkings of earlier prophecies) to be attributed to Thomas to enhance their authority, as seen in collections of prophecies which were printed, the earliest surviving being a chapbook entitled "The Whole Prophecie of Scotland, England, etc." (1603).

Descriptions and paraphrases of Thomas's prophecies were given by various Scottish historians of yore, though none of them quoted directly from Thomas.

Walter Scott was familiar with rhymes purported to be the Rhymer's prophecies in the local popular tradition, and published several of them. Later Robert Chambers printed additional collected rhyme prophecies ascribed to Thomas, in Popular Rhymes (1826).

The Weeping Stones Curse:

The ballad (Roud 219) around the legend of Thomas was catalogued Child Ballad #37 "Thomas the Rymer," by Francis James Child in 1883. Child published three versions, which he labelled A, B and C, but later appended two more variants in Volume 4 of his collection of ballads, published in 1892. Some scholars refer to these as Child's D and E versions. Version A, which is a Mrs Brown's recitation, and C, which is Walter Scott's reworking of it, were together classed as the Brown group by C.E. Nelson, while versions B, D, E are all considered by Nelson to be descendants of an archetype that reduced the romance into ballad form in about 1700, and classed as the 'Greenwood group'. (See §Ballad sources).

Child provided a critical synopsis comparing versions A, B, C in his original publication, and considerations of the D, E versions have been added below.

The brief outline of the ballad is that while Thomas is lying outdoors on a slope by a tree in the Erceldoune neighborhood, the queen of Elfland appears to him riding upon a horse and beckons him to come away. When he consents, she shows him three marvels: the road to Heaven, the road to Hell, and the road to her own world (which they follow). After seven years, Thomas is brought back into the mortal realm. Asking for a token by which to remember the queen, he is offered the choice of having powers of harpistry, or else of prophecy, and of these he chooses the latter.

The scene of Thomas's encounter with the elf-queen is "Huntly Bank" and the "Eildon Tree" (versions B, C, and E) or "Farnalie" (version D) All these refer to the area of Eildon Hills, in the vicinity of Earlston: Huntly Bank was a slope on the hill and the tree stood there also, as Scott explained: Emily B. Lyle was able to localize "farnalie" there as well.

The queen wears a skirt of grass-green silk and a velvet mantle, and is mounted either on a milk-white steed (in Ballad A), or on a dapple-gray horse (B, D, E and R (the Romance)). The horse has nine and fifty bells on each tett (Scots English. "lock of matted hair") on its mane in A, nine hung on its mane in E, and three bells on either side of the bridle in R, whereas she had nine bells in her hand in D, offered as a prize for his harping and carping (music and storytelling).

Thomas mistakenly addresses her as the "Queen of Heaven" (i.e. the Virgin Mary), which she corrects by identifying herself as "Queen of fair Elfland" (A, C). In other variants, she reticently identifies herself only as "lady of an unco land" (B), or "lady gay" (E), much like the medieval romance. But since the unnamed land of the queen is approached by a path leading neither to Heaven nor Hell, etc., it can be assumed to be "Fairyland," to put it in more modern terminology.

In C and E, the queen dares Thomas to kiss her lips, a corruption of Thomas's embrace in the romance that is lacking in A and B though crucial to a cogent plot, since "it is contact with the fairy that gives her the power to carry her paramour off" according to Child. Absent in the ballads also is the motif of the queen losing her beauty (Loathly lady motif): Child considered that the "ballad is no worse, and the romance would have been much better" without it, "impressive" though it may be, since it did not belong in his opinion to the "proper and original story," which he thought was a blithe tale like that of Ogier the Dane and Morgan le fay. If he chooses to go with her, Thomas is warned he will be unable to return for seven years (A, B, D, E). In the romance the queen's warning is "only for a twelvemonth", but he overstays by more than three (or seven) years.

Then she wheels around her milk-white steed and lets Thomas ride on the crupper behind (A, C), or she rides the dapple-gray while he runs (B, E). He must wade knee-high through a river (B, C, E), exaggerated as an expanse of blood (perhaps "river of blood"), in A. They reach a "garden green," and Thomas wants to pluck a fruit to slake his hunger but the queen interrupts, admonishing him that he will be accursed or damned (A, B, D, E). The language in B suggests this is "the fruit of the Forbidden Tree", and variants D, E call it an apple. The queen provides Thomas with food to sate his hunger.

The queen now tells Thomas to lay his head to rest on her knee (A, B, C), and shows him three marvels ("ferlies three"), which are the road to Hell, the road to Heaven, and the road to her homeland (named Elfland in A). It is the road beyond the meadow or lawn overgrown with lilies that leads to Heaven, except in C where the looks deceive and the lily road leads to Hell, while the thorny road leads to Heaven.

The queen instructs Thomas not to speak to others in Elfland, and to allow her to do all the talking. In the end, he receives as present "a coat of the even cloth, and a pair of shoes of velvet green" (A) or "tongue that can never lie" (B) or both (C). Version E uniquely mentions the Queen's fear that Thomas may be chosen as "teinding unto hell", that is to say, the tithe in the form of humans that Elfland is obliged to pay periodically. In the romance, the Queen explains that the collection of the "fee to hell" draws near, and Thomas must be sent back to earth to spare him from that peril. (See § Literary criticism for further literary analysis.)

The ballad was first printed by Walter Scott (1803), and then by Robert Jamieson (1806). Both used Mrs Brown's manuscript as the underlying source. Child A is represented by Mrs Brown's MS and Jamieson's published version (with only slight differences in wording). Child C is a composite of Mrs Brown's and another version. In fact, 13 of the 20 stanzas are the same as A, and although Scott claims his version is from a "copy, obtained from a lady residing not far from Ercildoun" corrected using Mrs Brown's MS, Nelson labels the seven different stanzas as something that is "for most part Scott's own, Gothic-romantic invention".

Child B is taken from the second volume of the Campbell manuscripts entitled "Old Scottish Songs, Collected in the Counties of Berwick, Roxburgh, Selkirk & Peebles", dating to ca. 1830. The Leyden transcript, or Child "D" was supplied to Walter Scott before his publication, and influenced his composition of the C version to some degree. The text by Mrs Christiana Greenwood, or Child "E" was "sent to Scott in May of 1806 after reading his C version in the Minstrelsey, and was dated by Nelson as an "early to mid-eighteenth-century text". These two versions were provided to Scott and were among his papers at Abbotsford.

Mrs Brown, also known as Anna Gordon or Mrs Brown of Falkland (1747–1810), who was both Scott's and Jamieson's source, maintained that she had heard them sung to her as a child. She had learned to sing a repertoire of some three dozen ballads from her aunt, Mrs Farquheson. Mrs Brown's nephew Robert Eden Scott transcribed the music, and the manuscript was available to Scott and others. However different accounts have been given, such as "an old maid-servant who had been long as the nursemaid being the one to teach Mrs Brown."

In Minstrelsy, Walter Scott published a second part to the ballad out of Thomas's prophecies, and yet a third part describing Thomas's return to Elfland. The third part was based on the legend with which Scott claimed to be familiar, telling that "while Thomas was making merry with his friends in the Tower of Ercildoune," there came news that "a hart and hind... was parading the street of the village." Hearing this, Thomas got up and left, never to be seen again, leaving a popular belief that he had gone to Fairyland but was "one day expected to revisit earth". Murray cites Robert Chambers's suspicion that this may have been a mangled portrayal of a living local personage, and gives his own less marvellous traditional account of Thomas's disappearance, as he had received it from an informant.

In Walter Scott's "Third Part" to the ballad, Thomas finds himself in possession of a "elfin harp he won" in Fairyland in a minstrel competition. This is a departure both from the traditional ballad and from the medieval romance, in which the queen tells Thomas to choose whether "to harpe or carpe," that is, to make a choice either of the gift of music or of the gift of speech. The "hart and hind" is now being sung as being "white as snow on Fairnalie" (Farnalie has been properly identified by Lyle, as discussed above). Some prose retellings incorporate some features derived from this third part (See §Retellings).

The traditional singer Duncan Williamson, a Scottish traveller who learned his songs from his family and fellow travellers, had a traditional version of the ballad which he was recorded singing on several occasions. One recording (and discussion of the song) can be heard on the Tobar an Dualchais website.

The surviving medieval romance is a lengthier account which agrees with the content of the ballad.

The romance opens in the first person (migrating to the third), but probably is not genuinely Thomas's own work. Murray dated the authorship to "shortly after 1400, or about a hundred years after Thomas's death", but more recent researchers set the date earlier, to the (late) 14th century. The romance often alludes to "the story," as if there had been a preceding recension, and Child supposed that the "older story," if any such thing actually existed, "must be the work of Thomas".

As in ballad C, Huntley banks is the locale where Thomas made sighting of the elfin lady. The "Eldoune, Eldone tree (Thornton, I, 80, 84)" is also mentioned as in the ballad. Thomas is captivated by her, addressing her as queen of heaven, and she answers she is not so lofty, but hints she is of fairy kind. Thomas makes proposition, but she warns him off saying that the slightest sin will undo her beauty. Thomas is undaunted, so she gives the "Mane of Molde" (i.e. Man of Earth; mortal man) (I, 117) consent to marry her and to accompany her.

"Seven tymes by hyr he lay," (I, 124), but she transforms into a hideous hag immediately after lying with him, and declares he shall not see "Medill-erthe" (I,160) for a twelvemonth ("twelmoneth", "xij Mones" vv.152, 159). As in the ballad, the lady points out one way towards heaven and another towards hell during their journey to her dominion (ca.200–220). The lady is followed by greyhounds and "raches" (i.e. scent dogs) (249–50). On arrival, Thomas is entertained with food and dancing, but then the lady tells him he must leave. To Thomas, his sojourn seems to last for only three days, but the lady tells him that three years ("thre ȝere"), or seven years ("seuen ȝere"), have passed (284–6) (the manuscripts vary), and he is brought back to the Elidon tree.

Fytte II is mostly devoted to prophecies. In the opening, Thomas asks for a token by which to remember the queen, and she offers him the choice of becoming a harper or a prophet ("harpe or carpe"). Rather than the "instrumental" gift, Thomas opts for the "vocal (rather oral) accomplishments." Thomas asks her to abide a bit and tell him some ferlys (marvels). She now starts to tell of future battles at Halidon Hill, Bannockburn, etc., which are easily identifiable historic engagements. (These are tabulated by Murray in his introduction.)

The prophecies of battles continue into Fytte III, but the language becomes symbolic. Near the end Thomas asks why Black Agnes of Dunbar (III, 660) imprisoned him, and she predicts her death. This mention of Black Agnes is an anachronism, Thomas of Erceldoune having lived a whole generation before her, and she was presumably confused with an earlier Countess of the March.

The medieval romance survives complete or in fragments in five manuscripts, the earliest of which is the Lincoln codex compiled by Robert Thornton:

All these texts were edited in parallel by J. A. H. Murray in The Romance and Prophecies of Thomas of Erceldoune (1875).

The Cotton MS. gives an "Incipit prophecia Thome Arseldon" and an "Explicit prophetia thome de Arseldoune", thus this was the version that Walter Scott excerpted as Appendix. The Sloan MS. begins the second fytte with: "Heare begynethe þe ijd fytt I saye / of Sir thomas of Arseldon," and the Thornton MS. gives the "Explicit Thomas Of Erseldowne" after the 700th line.

The romance dates from the late 14th to the early 15th century (see below), while the ballad texts available do not antedate ca. 1700-1750 at the earliest. The preponderance of opinion seems to be that the romance gave rise to the ballads (in their existing forms) at a relatively late date, though some disagree with this view.

Walter Scott stated that the romance was "the undoubted original", the ballad versions having been corrupted "with changes by oral tradition". Murray flatly dismisses this inference of oral transmission, characterizing the ballad as a modernization by a contemporary versifier. Privately, Scott also held his "suspicion of modern manufacture."

C. E. Nelson argued for a common archetype (from which all the ballads derive), composed around the year 1700 by "a literate individual of antiquarian bent" living in Berwickshire. Nelson starts off with a working assumption that the archetype ballad, "a not too remote ancestor of [Mrs] Greenwood['s version]" was "purposefully reduced from the romance". What made his argument convincing was his observation that the romance was actually "printed as late as the seventeenth century" (a printing of 1652 existed, republished Albrecht 1954), a fact missed by several commentators and not noticed in Murray's "Published Texts" section.

The localization of the archetype to Berwickshire is natural because the Greenwood group of ballads (which closely abide by the romance) belong to this area, and because this was the native place of the traditionary hero, Thomas of Erceldoune. Having made his examination, Nelson declared that his assumptions were justified by evidence, deciding in favour of the "eighteenth-century origin and the subsequent tradition of [the ballad of] 'Thomas Rhymer'", a conclusion applicable not only to the Greenwood group of ballads but also to the Brown group. This view is followed by Katharine Mary Briggs's folk-tale dictionary of 1971, and David Fowler.

From the opposite point of view, Child thought that the ballad "must be of considerable age", even though the earliest available to him was datable only to ca. 1700–1750. E. B. Lyle, who has published extensively on Thomas the Rhymer, presents the hypothesis that the ballad had once existed in a very early form upon which the romance was based as its source. One supporter of this view is Helen Cooper who remarks that the ballad "has one of the strongest claims to medieval origins"; another is Richard Firth Green who states that "continuous oral transmission is the only credible explanation". However, both Cooper and Green draw these conclusions under the mistaken assumption that the "romance... had not yet been printed at the time of Mrs Brown's performance".

In the romance, the queen declares that Thomas has stayed three years but can remain no longer, because "the foul fiend of Hell will come among the (fairy) folk and fetch his fee" (modernized from Thornton text, vv.289–290). This "fee" "refers to the common belief that the fairies "paid kane" to hell, by the sacrifice of one or more individuals to the devil every seventh year." (The word teind is actually used in the Greenwood variant of Thomas the Rymer: "Ilka seven year, Thomas, / We pay our teindings unto hell, ... I fear, Thomas, it will be yerself".) The situation is akin to the one presented to the title character of "Tam Lin" who is in the company of the Queen of Fairies, but says he fears he will be given up as the tithe (Scots: teind or kane) paid to hell. The common motif has been identified as type F.257 "Tribute taken from fairies by fiend at stated periods" except that while Tam Lin must devise his own rescue, in the case of the Rymer, "the kindly queen of the fairies will not allow Thomas of Erceldoune to be exposed to this peril, and hurries him back to earth the day before the fiend comes for his due". J. R. R. Tolkien also alludes to the "Devil's tithe" as concerns the Rhymer's tale in a passing witty remark

It has been suggested that John Keats's poem La Belle Dame sans Merci borrows motif and structure from the legend of Thomas the Rhymer.

Washington Irving, while visiting Walter Scott, was told the legend of Thomas the Rhymer, and it became one of the sources for Irving's short story Rip van Winkle.

There have been numerous prose retelling of the ballad or legend.

John Tillotson's version (1863) with "magic harp he had won in Elfland" and Elizabeth W. Greierson's version (1906) with "harp that was fashioned in Fairyland" are couple of examples that incorporate the theme from Scott's Part Three of Thomas vanishing back to Elfland after the sighting of a hart and hind in town.

Barbara Ker Wilson's retold tale of "Thomas the Rhymer" is a patchwork of all the traditions accrued around Thomas, including ballad and prophecies both written and popularly held.

Additional, non-exhaustive list of retellings as follows:

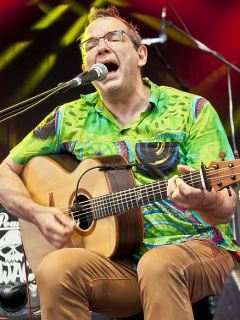

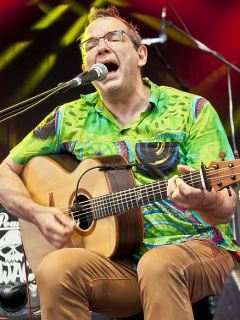

Listen to True Thomas from: Cara

Watch Thomas the Rhymer / True Thomas from: Steeleye Span, Saro Lynch Lyrics (© Mainly Norfolk): Thomas the Rhymer

The False Lover Won Back is Child ballad 218 (Roud 201). A maid pleads with her lover, who tells her that he is going to woo a fairer lady, and she can choose another man for all he cares. She chases after him on foot. As they reach towns, he tries to bribe her with gifts, to leave him, but at the third town, he has fallen in love with her again. As her last gift he purchases a wedding gown.

Listen to The False Lover Won Back from: Cara, Malinky

Watch The False Lover Won Back from: Greenhouse, Siobhan Miller Lyrics (© Mainly Norfolk): The False Lover Won Back

|

Malinky recorded The False Lover Won Back on 3 Ravens (2002):

»Karine [Polwart] set the lyrics to the pipe march Mary's Dream, which she learned from ace-piper Mike Katz. The lyrics she found in the Greig-Duncan collection (which inspired our first album Last Leaves). And when she finally checked out Cilla and Artie's version of Billy Taylor (thanks to Steve being at Mark's house, seeing Mark's fiancée Islay's Mum's bloke Dave's record collection—follow?) she found this song on the same album (learned from Jimmy Hutchison of South Uist). Spooky! Thanks to them for singing good songs in the first place. Thanks also to Harry F from Sparks, Nevada.«

|

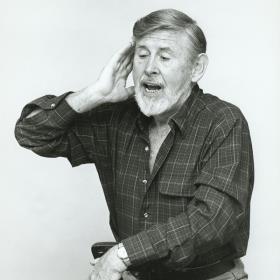

Ewan MacColl and Peggy Seeger recorded The False Lover Won Back on Classic Scots Ballads (1956):

»Outside of Scotland, this ballad is rarely found. Child knew it in only two versions, both from the North of Scotland. The ballad appears to be unknown in England and has been

reported in America in but a few variants. In Scotland, however, the ballad seems to have retained it popularity, for it is still sung widely by Aberdeenshire ballad singers.

This version was learned from Gavin Greig's Last Leaves of Traditional Ballads and Ballad Airs (Aberdeen, 1925).«

|

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: October 2021.

Photo Credits:

(1)-(9),(16) Cara,

(10),(20) Ewan MacColl,

(11) Ellen Kushner "Thomas the Rhymer",

(12) Maddy Prior (Steeleye Span),

(13)-(14) Joseph Noel Paton "Thomas the Rhymer and the Queen of Faery", "The Fairy Queen",

(18) Frankie Armstrong,

(19) Malinky

(unknown/website);

(15) "Thomas the Rhymer!

(by ABC Notations);

(17) "The False Lover Won Back"

(by 8notes).