FolkWorld Issue 39 07/2009;

Article

The Craic Is Ninety

Happy Birthday, Pete Seeger!

On May 3rd, New York's Madison Square Garden was packed with 18,000 people

who gathered joyfully to celebrate Pete Seeger's 90th birthday.

Pete Seeger - a legendary folk singer, a living history.

He was one of the principal inspirations for younger performers in the folk revival of the 1960s, and

he embodies the 20th century struggles for civil and workers' right and

for peace and environmental issues as nobody else.

|

Pete Seeger, * 03.05.1919, Patterson, New York, USA.

Once blacklisted for being unafraid to voice his opinions,

the key figure of the 20th century American folk music revival

was recently named one of America's Living Legends by the Library of Congress.

In 1936 Pete had heard the five-string banjo for the first time, becoming an accomplished player

and later writing his classic "How to Play the Five-String Banjo."

In 1939 he took a job assisting Alan Lomax,

sifting through commercial race and hillbilly music and selecting recordings that best represented traditional folk music.

Pete became the founding member of two highly influential folk groups: The Almanac Singers and The Weavers.

The Almanac Singers, featuring Woody Guthrie, was a loosely organized musical collective

performing union and pacifist songs. Pete co-wrote "If I Had a Hammer" with Lee Hays.

In 1950 the Almanacs were reconstituted as The Weavers, named after a play by Gerhart Hauptmann.

In the red-baiting 50s, the Weavers' repertoire was less overtly topical.

They enjoyed success with a sweetened version of Leadbelly's "Goodnight, Irene".

Other Weaver hits included "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" and the South African Zulu song "Wimoweh".

The Weavers's career was abruptly halted in 1953 when blacklisting

prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and their bookings were canceled.

Pete Seeger went on, writing songs such as

"Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and "Turn, Turn, Turn", adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

His variation of an old spiritual, "We Shall Overcome," became the anthem of the 1960s civil rights movement.

In 2008 Pete made a rare appearance on the David Letterman

Late Show singing Don't say it can't be done, the battle's just begun, take it from Dr. King you too can

learn to sing so drop the gun, and

Appleseed Recordings released "At 89," Seeger's first studio album in 12 years.

In January 2009 Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen and the crowd in singing

the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's inaugural concert.

On May 3, 18,000 people and dozens of musicians gathered at New York's Madison Square Garden to celebrate Pete's

90th birthday, the proceeds from the event are to benefit the Clearwater Environmental Foundation,

a non-profit organization created to protect the Hudson River.

Pete Seeger, * 03.05.1919, Patterson, New York, USA.

Once blacklisted for being unafraid to voice his opinions,

the key figure of the 20th century American folk music revival

was recently named one of America's Living Legends by the Library of Congress.

In 1936 Pete had heard the five-string banjo for the first time, becoming an accomplished player

and later writing his classic "How to Play the Five-String Banjo."

In 1939 he took a job assisting Alan Lomax,

sifting through commercial race and hillbilly music and selecting recordings that best represented traditional folk music.

Pete became the founding member of two highly influential folk groups: The Almanac Singers and The Weavers.

The Almanac Singers, featuring Woody Guthrie, was a loosely organized musical collective

performing union and pacifist songs. Pete co-wrote "If I Had a Hammer" with Lee Hays.

In 1950 the Almanacs were reconstituted as The Weavers, named after a play by Gerhart Hauptmann.

In the red-baiting 50s, the Weavers' repertoire was less overtly topical.

They enjoyed success with a sweetened version of Leadbelly's "Goodnight, Irene".

Other Weaver hits included "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" and the South African Zulu song "Wimoweh".

The Weavers's career was abruptly halted in 1953 when blacklisting

prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and their bookings were canceled.

Pete Seeger went on, writing songs such as

"Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and "Turn, Turn, Turn", adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

His variation of an old spiritual, "We Shall Overcome," became the anthem of the 1960s civil rights movement.

In 2008 Pete made a rare appearance on the David Letterman

Late Show singing Don't say it can't be done, the battle's just begun, take it from Dr. King you too can

learn to sing so drop the gun, and

Appleseed Recordings released "At 89," Seeger's first studio album in 12 years.

In January 2009 Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen and the crowd in singing

the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's inaugural concert.

On May 3, 18,000 people and dozens of musicians gathered at New York's Madison Square Garden to celebrate Pete's

90th birthday, the proceeds from the event are to benefit the Clearwater Environmental Foundation,

a non-profit organization created to protect the Hudson River.

Pete Seeger @ FolkWorld:

FW #21,

#26,

#29,

#35,

#36

Pete Seeger & Bruce Springsteen

Pete Seeger & Bruce Springsteen

@ Barack Obama's Inaugural Concert

www.peteseeger.net

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pete_Seeger

|

While it could be stated that Woody Guthrie served as a spiritual godfather to the folk revival,

it was really one of his close friends, the ex-Harvard student Pete Seeger,

who laid many of the actual foundations of the movement. His father, Charles,

had written extensively on American folk music. His son took up the cause

wholeheartedly, but chose to take action rather than simply write; travelling

around the South and the West, Seeger

gained a sense of affinity wit the 'ordinary' American people, and a desire

to keep their cultures and songs alive through performance.

(Gillian Mitchell)

Peter Seeger is possessed of that rarest of human qualities - the inquiring mind.

This gentle and at the same time fiery and unbeatable spirit pervades his music, his friendships,

his beanpole body and his thought. His performances are true to our folk musicians faithfully and

sensitively. (Alan Lomax)

There isn't enough space in this whole issue to list all the wonderful things Pete Seeger has done

for individuals, groups, and for us in the whole world. Even the fish in the sea and the birds in the

air would thank him if they knew. I think he is very probably the main reason for the folk revival in

this country. He is our music teacher. All of us who were so carefully taught to hate music in school,

then learned to appreciate and understand it and what it's for with Pete Seeger. Pete is one of the

greatest of American patriots. I think he's one of the main reasons the Civil Rights and peace

movements attained the heights they did. He inspired us, or inspired the people who inspired us.

He was America's conscience in an unhopeful time. There is no way we can thank him enough.

(Michael Cooney)

I don't know where I'd be today if it wasn't for Pete Seeger. I can't say for sure, but I probably

wouldn't have started singing folk songs or playing the guitar and banjo.

I would not have had the

rich experiences, the life-long friendships, the world travel and all the other twists and turns my

life has taken during the forty years since I first heard Pete play. He

sang about all manner of things that I had never heard addressed before, and his energy and

engagement with the audience captivated me totally. I suddenly saw music in a whole new light,

realized that it could address social issues and relate to the joys and sorrows, the history and

universality, of the people. As I sang at the top of my lungs, I felt the thrill of being part of something vast and

important, a movement that was in the vanguard, an in-group that was going to change the world.

The next day, I went out and bought a guitar. I found out about Washington Square, went to "hoots"

and folk concerts, learned hundreds of songs. I sang with the image of Pete peering over my shoulder.

I sang the songs he sang, tried to approximate his stance, his instrumental style, and his

cheer-leader's approach to group singing. I sang only songs I thought Pete would approve of,

and wore his records thin. I sang of solidarity with unions, even

though I wasn't a worker; peasant chants, and I certainly wasn't a peasant (never even met one);

sang songs in bad Korean, unintelligible Swahili, broken Hebrew, and other languages that Pete sang in.

I was one with the miners, the farm hands, the pioneers, the whalers (still politically correct in

those days), the "masses."

This all seems naive and hopelessly out-dated, but somewhere deep

inside my soul the eternal optimism of Pete's songs still rings true.

And even if that new world doesn't materialize

in our lifetime, I know that one sixteen-year-old's life was irrevocably changed by the revelation

of a lone man on a wide stage, singing his songs and becoming one with his audience.

(Happy Traum)

The term folksinger is applied to strummers and crooners of all types and stripes today, but it is

perhaps more apt for Pete Seeger than for any other performer.

Seeger offers what may be the world’s most extensive repertoire of protest songs, work songs, modern

ballads and traditional material from Britain, Europe and Africa. His performances involve the

audience as much as his own artistry, for he is the long-crowned master of the "sing-along" — and

his concerts are models of audience participation.

Seeger is, perhaps, the most humanitarian and society-conscious performer of modern times, and he was

a model for the protest singers of a later day, notably Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

(Edgar Koshatka)

The term folksinger is applied to strummers and crooners of all types and stripes today, but it is

perhaps more apt for Pete Seeger than for any other performer.

Seeger offers what may be the world’s most extensive repertoire of protest songs, work songs, modern

ballads and traditional material from Britain, Europe and Africa. His performances involve the

audience as much as his own artistry, for he is the long-crowned master of the "sing-along" — and

his concerts are models of audience participation.

Seeger is, perhaps, the most humanitarian and society-conscious performer of modern times, and he was

a model for the protest singers of a later day, notably Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

(Edgar Koshatka)

I first heard of Pete Seeger through a right-wing Lutheran publication that complained that he had

been invited to sing at a Walther League convention (the youth organization of the Lutheran

Church-Missouri Synod) in 1964 or so. I remember asking my parents (I was about 11) why everyone was

so upset about a "former communist" singing to the Walther Leaguers. "How could singing songs hurt

anybody's faith?" I asked. The insipid answer was that we should have found a good Lutheran

folk-singer.

Years later -- April 22, 1971 to be precise -- I heard Pete sing "Last Train to Nuremberg" at the

big pre-May Day rally in Washington, D.C. I was electrified, and began to realize how naive my

question had been: Music CAN be dangerous, especially to those whose position and influence rests

on violence, coercion, lies, and fear. The right wingers were exactly right to be afraid of Pete's

influence on young people. Hearing him sing Malvina Reynold's "Little Boxes" and "God Bless the Grass"

was like a hyper-link to the idea that the world could be a better place if only we took

responsibility for making it so.

Since then, I've learned to play the banjo (sort of) through his book, lead singing in groups large

and small, and pass on the joy and power of music to many others, all small flowers from the seeds

he scattered.

(Paul Landskroener)

Because of his indefatigable efforts, folk music, instead of dying out, came to life again. Today

millions all over the world associate folk music with that man — Pete Seeger.

Pete Seeger has been a guiding force in folk music for so many years that sometimes we take him for

granted. His accomplishments are many, but perhaps the most important one has been his inspiring

countless "Johnny Appleseed, Jr.’s" to make their own kind of music.

(Jim Capaldi)

I have many heroes, but if I had to pick one it would have to be Pete Seeger. Because he is a man

of principle, because he has had the courage of his convictions, because he is an inspiringly humane,

self-effacing and dedicated human being, because he has a sense of humor about himself and life, and

because he loves to create art. He's a great man. Every musician activist that I know

I said, 'Where did you get this idea from?' And the first name that

came out of their mouths was Pete Seeger.

(David Crosby)

|

For Pete

he's a sailor

a bumbling, crafty, thoughtful, dreaming

chopstick drummer

a lover

a brightly colored creature

a root that knuckles through the soil

to reach you

a sculptured banjo body

shedding humane thoughts

on careless scraps of paper leaves

a voice of fiber bark

tender as an April bud

a raging, flaming, autumn fire

Tall

Strong

bending in the breeze, but growing

natural as wood

a shady place

for all these children of the son

(Don McLean)

|

When I was 15 years old, my dad, who worked at Emory University in Atlanta, gave my friend Cynthia

and me two tickets to see this guy named Pete Seeger, a folk singer who I had never heard of.

(I think that my dad thought that folk singers were wholesome!). Cynthia and I piled into a small

auditorium on campus, and sat on the floor. As we sat there, a college student came to the microphone

and told us that earlier that day, the National Guard had shot and killed four students at a little

college in Ohio called Kent State, during a protest against the war in Vietnam. Then, Pete Seeger

came out and sang his heart out, and we all sang with him. That night my life changed, and I have

never been the same. I have been to his concerts since then, but I don't think that anything will

ever match the power, and the sadness, and the awe that we all felt that night. Pete Seeger and I

share this stupid belief that children should be nurtured, and not shot down by their own government.

The last couple of times that I have seen Mr. Seeger on television, he has mentioned that he was

losing his voice in his advanced age. He isn't losing his "voice," at all. It's right here.

(Larry Ortega)

As Woody Guthrie began to succumb to Huntington's disease, Pete was more or less enthroned as the titular head of the folk music community and the progressive way of life.

Hating Pete Seeger was a cottage industry for certain people back in the fifties and early sixties.

The story was always the same. Pete and his songs and the message they portrayed were dangerous.

The Establishment's energies were so concentrated on getting at Pete that they couldn't see what was happening right under their noses.

Groups like the Kingston Trio took Pete's songs and made them top-forty hits.

(Paul Colby)

He was one of the few people who invoked the First Amendment in front of the House Un-American

Activities Committee (HUAC). Everyone else had said the Fifth Amendment, the right against

self-incrimination, and then they were dismissed. What Pete did, and what some other very

powerful people who had the guts and the intestinal fortitude to stand up to the committee and say,

"I'm gonna invoke the First Amendment, the right of freedom of association..."

I was actually in law school when I read the case of Seeger v. United States, and it really changed

my life, because I saw the courage of what he had done and what some other people had done by

invoking the First Amendment, saying, "We're all Americans. We can associate with whoever we want

to, and it doesn't matter who we associate with." That's what the founding fathers set up democracy

to be. So I just really feel it's an important part of history that people need to remember.

(Jim Musselman)

Although I am a "radical right wing Republican Christian" who disagrees sharply with Seeger on many

political views, I could never doubt his genuine love for his fellow man or his country. I think in

some ways, his music reflects one of the basic platforms of the true Christian message. Love thy

neighbor. Politics aside, how could you not love that voice and that overstretched banjo neck.

I'd give anything to just sit by him and strum along for a long while.

(Fred Pate)

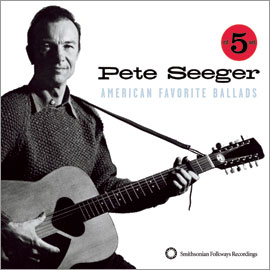

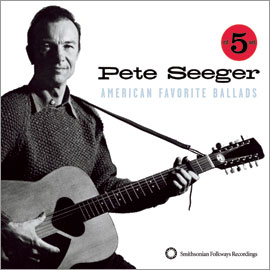

Pete Seeger "American Favorite Ballads, Vols. 1-5"

Pete Seeger "American Favorite Ballads, Vols. 1-5"

Label:

Smithsonian Folkways;

SFW40155; 2009

Pete Seeger’s life, music, and legacy encapsulate nearly a century of American history and culture. He has immersed himself in folk music and used it, like Johnny Appleseed, to "plant the seeds of a better tomorrow in the homes across our land."

The physical box-set version includes 139 tracks and 5 CDs, each with its own booklet of extensive notes, for nearly 6 hours of music.

The digital download version includes the 139 songs on the CD version plus two additional previously unreleased songs.

Buffalo Gals,

Oh Mary Don't You Weep

Buffalo Gals,

Oh Mary Don't You Weep

|

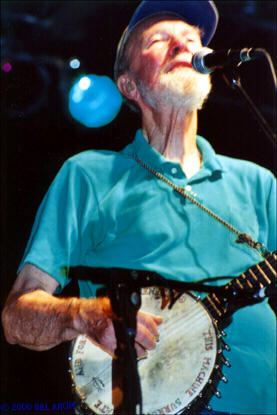

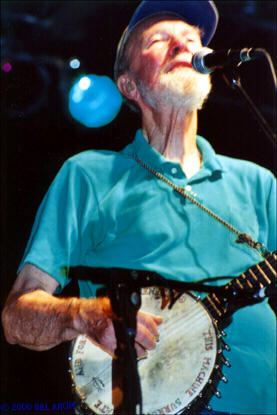

Photo Credits:

(1)-(2) Pete Seeger (by Wikipedia);

(3) American Favorite Ballads, Vols. 1-5

(by Smithsonian Folkways).

© The Mollis - Editors

of FolkWorld; Published 07/2009

All material published in FolkWorld is © The

Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews

and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source

and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors

for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.

FolkWorld - Home of European Music

Layout & Idea of FolkWorld © The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld

![]() Pete Seeger, * 03.05.1919, Patterson, New York, USA.

Once blacklisted for being unafraid to voice his opinions,

the key figure of the 20th century American folk music revival

was recently named one of America's Living Legends by the Library of Congress.

In 1936 Pete had heard the five-string banjo for the first time, becoming an accomplished player

and later writing his classic "How to Play the Five-String Banjo."

In 1939 he took a job assisting Alan Lomax,

sifting through commercial race and hillbilly music and selecting recordings that best represented traditional folk music.

Pete became the founding member of two highly influential folk groups: The Almanac Singers and The Weavers.

The Almanac Singers, featuring Woody Guthrie, was a loosely organized musical collective

performing union and pacifist songs. Pete co-wrote "If I Had a Hammer" with Lee Hays.

In 1950 the Almanacs were reconstituted as The Weavers, named after a play by Gerhart Hauptmann.

In the red-baiting 50s, the Weavers' repertoire was less overtly topical.

They enjoyed success with a sweetened version of Leadbelly's "Goodnight, Irene".

Other Weaver hits included "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" and the South African Zulu song "Wimoweh".

The Weavers's career was abruptly halted in 1953 when blacklisting

prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and their bookings were canceled.

Pete Seeger went on, writing songs such as

"Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and "Turn, Turn, Turn", adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

His variation of an old spiritual, "We Shall Overcome," became the anthem of the 1960s civil rights movement.

In 2008 Pete made a rare appearance on the David Letterman

Late Show singing Don't say it can't be done, the battle's just begun, take it from Dr. King you too can

learn to sing so drop the gun, and

Appleseed Recordings released "At 89," Seeger's first studio album in 12 years.

In January 2009 Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen and the crowd in singing

the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's inaugural concert.

On May 3, 18,000 people and dozens of musicians gathered at New York's Madison Square Garden to celebrate Pete's

90th birthday, the proceeds from the event are to benefit the Clearwater Environmental Foundation,

a non-profit organization created to protect the Hudson River.

Pete Seeger, * 03.05.1919, Patterson, New York, USA.

Once blacklisted for being unafraid to voice his opinions,

the key figure of the 20th century American folk music revival

was recently named one of America's Living Legends by the Library of Congress.

In 1936 Pete had heard the five-string banjo for the first time, becoming an accomplished player

and later writing his classic "How to Play the Five-String Banjo."

In 1939 he took a job assisting Alan Lomax,

sifting through commercial race and hillbilly music and selecting recordings that best represented traditional folk music.

Pete became the founding member of two highly influential folk groups: The Almanac Singers and The Weavers.

The Almanac Singers, featuring Woody Guthrie, was a loosely organized musical collective

performing union and pacifist songs. Pete co-wrote "If I Had a Hammer" with Lee Hays.

In 1950 the Almanacs were reconstituted as The Weavers, named after a play by Gerhart Hauptmann.

In the red-baiting 50s, the Weavers' repertoire was less overtly topical.

They enjoyed success with a sweetened version of Leadbelly's "Goodnight, Irene".

Other Weaver hits included "Kisses Sweeter Than Wine" and the South African Zulu song "Wimoweh".

The Weavers's career was abruptly halted in 1953 when blacklisting

prompted radio stations to refuse to play their records and their bookings were canceled.

Pete Seeger went on, writing songs such as

"Where Have All the Flowers Gone" and "Turn, Turn, Turn", adapted from the Book of Ecclesiastes.

His variation of an old spiritual, "We Shall Overcome," became the anthem of the 1960s civil rights movement.

In 2008 Pete made a rare appearance on the David Letterman

Late Show singing Don't say it can't be done, the battle's just begun, take it from Dr. King you too can

learn to sing so drop the gun, and

Appleseed Recordings released "At 89," Seeger's first studio album in 12 years.

In January 2009 Seeger joined Bruce Springsteen and the crowd in singing

the Woody Guthrie song "This Land Is Your Land" in the finale of Barack Obama's inaugural concert.

On May 3, 18,000 people and dozens of musicians gathered at New York's Madison Square Garden to celebrate Pete's

90th birthday, the proceeds from the event are to benefit the Clearwater Environmental Foundation,

a non-profit organization created to protect the Hudson River.

![]() Pete Seeger & Bruce Springsteen

Pete Seeger & Bruce Springsteen

The term folksinger is applied to strummers and crooners of all types and stripes today, but it is

perhaps more apt for Pete Seeger than for any other performer.

Seeger offers what may be the world’s most extensive repertoire of protest songs, work songs, modern

ballads and traditional material from Britain, Europe and Africa. His performances involve the

audience as much as his own artistry, for he is the long-crowned master of the "sing-along" — and

his concerts are models of audience participation.

Seeger is, perhaps, the most humanitarian and society-conscious performer of modern times, and he was

a model for the protest singers of a later day, notably Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

(Edgar Koshatka)

The term folksinger is applied to strummers and crooners of all types and stripes today, but it is

perhaps more apt for Pete Seeger than for any other performer.

Seeger offers what may be the world’s most extensive repertoire of protest songs, work songs, modern

ballads and traditional material from Britain, Europe and Africa. His performances involve the

audience as much as his own artistry, for he is the long-crowned master of the "sing-along" — and

his concerts are models of audience participation.

Seeger is, perhaps, the most humanitarian and society-conscious performer of modern times, and he was

a model for the protest singers of a later day, notably Bob Dylan and Joan Baez.

(Edgar Koshatka)