Having gone to the USA for my first, second, fourth, fifth, eighth and fourteenth choices, and Ireland for my third, Scotland for my sixth, England for my seventh, ninth, tenth and twelfth, Canada for my eleventh, and Australia for my thirteenth, I choose to go back to the Ireland again for my fifteenth.

People sometimes ask me what criteria do I use to decide on which songs to put under the microscope? For instance, do they have to be great songs? The answer is ‘no’ but it sure helps. Do they have to be songs I like? No, but again, it helps. That said, I guess it is possible I would have something to say about songs I actively disliked.

The key is in the last sentence: it is important that I have something to say. Just trotting out the lyrics and adding a bit of padding is not good enough.

Today’s choice of song is one that definitely ticks my ‘like’ box, but has always been a puzzle in some respects... but more on that later.

Let’s start by playing you the traditional song that Houston Collisson lifted to form much of the melody of The Mountains of Mourne. (Collisson was a successful Irish musician: a composer who had several smash hits on the London music hall.) Here is the old air Carrigdhoun played and sang by the peerless Mary O’Hara...

Very pleasant, but the lyrics do not really ‘do it’ for me... (my fault, I’m sure). Still, the melody was clearly a winner, and one understands the desire of Collisson and French to run with it, though significantly adapt it. Over a long professional relationship they generally got things right, when it came to the ‘creative process’. They tended to be ‘in sync’ with one another... even to the point of both leaving this world just seven days apart, in the year of 1920.

And so, let’s get down to business...

...when Percy French’s insightful words were put to Collisson’s variation of this melody, they knew they had a winner. French had originally called it The Mountains o’ Mourne... but from here onwards, I will call it ‘of Mourne’... since all the recordings I will cite, call it just that.

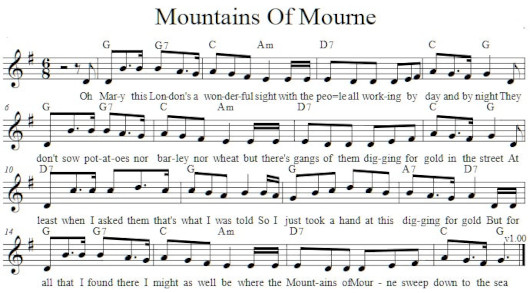

There are, as I hinted above, some aspects of this song that are a puzzle to me, and I will shortly explain. But for the moment, let’s start with the lyrics. And they incidentally are rarely ever the same from recording to recording...

Here are French’s original words...

The Mountains o' Mourne Oh, Mary, this London's a wonderful sight, With people all working by day and by night. Sure, they don't sow potatoes, nor barley, nor wheat, But there's gangs of them digging for gold in the street. At least when I asked them that's what I was told, So I just took a hand at this digging for gold, But for all that I found there I might as well be Where the Mountains o' Mourne sweep down to the sea. I believe that when writing a wish you expressed As to how the fine ladies in London are dressed, Well if you'll believe me, when asked to a ball, They don't wear no top to their dresses at all. Oh I've seen them meself and you could not in truth, Say if they were bound for a ball or a bath. Don't be starting such fashions, now, Mary, mo chroí, Where the Mountains o' Mourne sweep down to the sea. I've seen England's king from the top of a bus And I've never known him, but he means to know us. And tho' by the Saxon we once were oppressed, Still I cheered, God forgive me, I cheered with the rest. And now that he's visited Erin's green shore We'll be much better friends than we've been heretofore When we've got all we want, we're as quiet as can be Where the Mountains o' Mourne sweep down to the sea. You remember young Peter O'Loughlin, of course, Well, now he is here at the head of the Force. I met him today, I was crossing the Strand, And he stopped the whole street with a wave of his hand. And there we stood talkin' of days that are gone, While the whole population of London looked on. But for all these great powers he's wishful like me, To be back where the dark Mournes sweep down to the sea. There's beautiful girls here, oh, never you mind, With beautiful shapes nature never designed, And lovely complexions all roses and cream, But let me remark with regard to the same That if of those roses you ventured to sip, The colours might all come away on your lip, So I'll wait for the wild rose that's waiting for me In the place where the dark Mournes sweep down to the sea.

The third verse - on reconciliation between Dublin and London – got dropped by many performers from early on. In that verse incidentally, he talks of King Edward Vll’s visit to Ireland as follows...

And now that he's visited Erin's green shore

We'll be much better friends than we've been heretofore.

Now, this is a bit of a mystery to me. Most people date the song’s first publication as being in 1896... when Queen Victoria was still on the throne of the United Kingdom. And it was to be another five years before she would die. True, as Prince Albert, Edward Vll had visited Ireland a handful of times during his mother’s long lifetime, but Percy French here specifically talks about the King having visited... and that would put the song’s creation at 1903/4... since Edward Vll made his first visit to Ireland as King in July/August 1903.

But hey, whether that verse was added to the other words written in 1896, is I suppose a bit academic... since as I say, most early performers quickly dispensed with it, for reasons that are understandable, if regrettable... I mean to say given that the Easter Rising was only 13 years following the King’s first visit. (And it took a wonderful visit in May 2011 to Dublin by our late Queen Elizabeth to finally heal the wounds... ‘wonderful’ in the sense that this woman who had seen her much-loved cousin – and Prince Philip’s uncle - Lord Louis Mountbatten murdered by the IRA, still had the grace to apologise for British excesses down the years.)

The song owed its popularity in large measure to the great Australian bass-baritone, Peter Dawson. He first recorded it in 1931, and again in 1940. And when I was born in 1947, one of my earliest memories was listening to this very same shellac recording below, on an almost identical wind-up gramophone. A great singer was Dawson, and our copy of it fell victim a few years later (along with our whole shellac collection) to a freakish event in our tiny terraced house. Space being at a premium... one very hot summer, in an effort to safeguard the very fragile records from damage, my sister put them in the one bit of free space she could find... the coal-fired oven...!! I should add that such an oven – next to the empty fireplace - was deliciously cool in summer. Alas, summers in the Welsh Valleys are usually brief affairs, and come September and a cold spell, another family member made the disastrous decision to light the fire in the range...!!

We all clean forgot the shellac jewels my sister had stored for temporary safekeeping in the oven adjoining the hearth... and the first intimation we got, that things were amiss, was our puzzlement at the flow of black gunge through a tiny crack in the oven door.

Still... I suppose worse things happen at sea. And we quickly got over the ‘jewels’ we had lost, like the shellac recordings of Harry Lauder, Caruso and Nellie Melba... and my sister had the bonus of being able to imaginatively mould lots of the melting shellac into flower pots...!!

Here Dawson delivers the song in a reasonably convincing Irish accent: and set the standard really for non-Irish performers of the song... they too down the years would mainly mimic an Irish brogue, some more convincingly than others...

Here in 1940, the then hugely popular Webster Booth also makes a decent stab at singing in an accent that was not his own. The piano accompaniment incidentally, is by a man who later became synonymous with being accompanist to the stars of the classical stage like Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Victoria de los Ángeles, Kathleen Ferrier, Janet Baker and a host of others... Gerald Moore.

Here is a rare version with the reconciliation verse included...

And here is a humorous reply penned and sang by Alison Humphries...

I was very taken by these tiny primary school kids from six schools, (all with their music teachers facing them and urging them on) singing the song in the centre of Newcastle, County Down, in 2013. Needless to say, were Co. Down to be its own nation, then this song would assuredly be its national anthem...

I could have sworn that I had an LP of the great John McCormack singing the song, but evidently not: rumour has it that he refused to sing any Percy French song because he disapproved of what he saw as French’s mocking of the rustic Irishman... more of that later.

I certainly had an album featuring that fine Irish tenor Brendan O’Dowda’s respectable version...

But one version of this fine song is really pre-eminent: and that of course is Don McLean’s wonderful live version on BBC TV’s Old Grey Whistle Test. No pressure then Don: just a couple of million Brits watching you try to do justice to this fine song... and boy, you really deliver big time...

It is October 9th, 1973, at the BBC Television Theatre, Shepherd’s Bush, London. McLean is 28 years and one week old. His mastery of the song here is nonpareil. No need for a cod Irish accent: just divinely sensitive and authoritative guitar work, a sublimely intelligent approach to the lyric, and with his sweet voice taking a few delightful liberties with the melody as the song progresses. (His melodic ‘improvements’ were later aped by Keith Harkin’s vocal in the hugely popular Irish band Celtic Thunder... and Don was thus given the ultimate honour of hearing an Irishman hiding his Irish accent while singing the song... sooo like Don, did Keith try to sound. But not to my taste, alas.)

There are several postings of different performances of Don singing this song on YouTube... but none come remotely close to this. I would not mind betting that the BBC cameras here in October 1973 caught the almost impossibly handsome Don at the very peak of his powers: physically, intellectually and above all, musically.

Wasn’t that quite something? If only Percy French and Houston Collisson could have heard it. They would have just drooled...

Okay... let me move from talking about Don McLean, to looking at the song itself. And now we come to the puzzlement I expressed feeling, at the top of this piece...

You see, Percy French and Houston Collisson penned several humorous songs between them, and the common theme was sort of self- deprecating: making their rural fellow Irishmen appear pleasantly ‘away with the fairies’ so-to-speak... the total antithesis of the hard-bitten, streetwise, urban dweller. This to some extent they did with the English audience in mind: by pandering to their love of the jokes that poked fun of what Irishmen call the 'culchie': what in Scotland is called a 'teuchter' (sometimes spelt as 'cheuchter' and pronounced 'chookta' with a guttural 'k'... like the 'ch' in the word 'loch').

And although this song now, a century and a quarter later, is seen as a glorious heartfelt love letter, at the time when French wrote the words, methinks his intention was to make the listener chuckle, rather than try to subdue the lump in his throat.

Take the first verse... the culchie is unwise enough to ask a group of labourers why were they digging up the road (presumably to lay utility piping...gas, water, sewage?)... and is given the sardonic answer ‘we’re digging for gold’.

So if we are to believe our Percy, our Irish rustic...

just took a hand at this digging for gold.

Ha! A likely story.

But you can look at it conversely: the Irish have always been a poetical race... and he does not really expect his sweetheart recipient of this love letter to believe for one minute that he is digging for actual gold. He knows that she will read between the lines, and know that ‘gold’ simply meant a weekly wage enough to keep body and mind together in the big wicked city where thousands are starving. And he is telling her that he got a job labouring with them, and so not to worry about him struggling to survive.

And then we come to that beautiful second verse... and its plea to his Mary not to follow the fashions of those racy young women, who he sees every day in London. As he so wittily puts it...

Well if you'll believe me, when asked to a ball,

They don't wear no top to their dresses at all.

Oh I've seen them meself and you could not in truth,

Say if they were bound for a ball or a bath.

Those lines make me laugh out loud every time... and it is even more true in 2023, methinks.

The line that follows is most interesting in that two words fall victim to the Folk Tradition of people ‘singing what they hear’. And so it is that...

Don't be starting such fashions, now, Mary, mo chroí,

has got changed to what folk hear... if they do not speak Gaelic, they will hear ‘Mary McCree’ (with variations on the spelling), and not ‘Mary, my (sweet)heart’... which is the true translation from the Gaelic.

The third verse - the reconciliation verse – I have already covered. Sad that more people did not include it on their performance. Here is one group that did: Wall Street Crash....

And then the fourth verse, which has Percy again tempted to go for an easy laugh: here with the culchie bumping into a contemporary from his home village, and being amazed that he is now a London traffic policeman...

You remember young Peter O'Loughlin, of course,

Well, now he is here at the head of the Force.

I met him today, I was crossing the Strand,

And he stopped the whole street with a wave of his hand.

And he attributes O’Loughlin’s ability to ‘stop all the traffic’ (a lyric change there by Don to which I don’t object, though I am not sure it improves on Percy’s original), just by waving his hand, to the fact he must be ‘the head’ of the Metropolitan Police to have such great powers...!!

But does he really think this? Of course not. It is another lovely bit of whimsy, and it seduces us for a nanosecond, but it is obviously another example of poetic licence. Incidentally, O’Loughlin - the name chosen by Percy French and favoured by most singers – gets his name changed to at least three different Irish names in various versions. Quite why is mystifying... I note that Don McLean sings ‘Denny McLaren’...

And then we come to the final verse... and I can think of no song with a greater last verse than this...

There's beautiful girls here, oh, never you mind,

With beautiful shapes nature never designed,

And lovely complexions all roses and cream,

But let me remark with regard to the same

That if of those roses you ventured to sip,

The colours might all come away on your lip,

So I'll wait for the wild rose that's waiting for me

In the place where the dark Mournes sweep down to the sea.

Although I have heard and sang this song a myriad times, that fourth line of the final verse always arrests me...

But let me remark with regard to the same

It is so wonderfully ‘matter-of-fact’: it is just the sort of line you would see in a letter from your family doctor or solicitor. Only songwriters blessed with genius would think of using such a formal line: it makes me think of Banjo Paterson’s use of such formalities in his wonderful Clancy Of The Overflow.

But oh, goodness gracious me... it is not the fourth line so much, as the sixth, that is the sheer knockout line: what a PUNCH that line delivers...!!

The colours might all come away on your lip just never fails to make me inhale deeply as a sign of my admiration for a real ‘bulls-eye’ hit. It really puts to bed all the impish teasing of ‘digging for gold’ and the ‘great powers’ of a traffic cop. Because here he gets serious with his Mary and tells her that she may not be the voluptuous creature that some London girls are, but points out that they are false... and you Mary are not... you are the genuine article.

As indeed is this great song.

[Dai Woosnam. Grimsby... 17/02/2023]

Photo Credits:

(1) Percy French 'The Mountains of Mourne' (watercolour);

(2) Dai Woosnam,

(3),(7) Percy French,

(4) Houston Collisson,

(5)-(6) Don McLean,

(8) 'The Mountains of Mourne'

(unknown/website).