Music of Africa, Part 1: Democratic Republic of the Congo, Senegal, The Gambia, and Mali.

African music is a tradition mainly played at gatherings at special occasions. The traditional Music of Africa, given the vastness of the continent, is historically ancient, rich and diverse, with different regions and nations of Africa having many distinct musical traditions. Music in Africa is very important when it comes to religion. Songs and music are used in rituals and religious ceremonies, to pass down stories from generation to generation, as well as to sing and dance to. Traditional music in most of the continent is passed down orally (or aurally) and is not written. In sub-Saharan African music traditions, it frequently relies on percussion instruments of every variety, including xylophones, djembes, drums, and tone-producing instruments such as the mbira or "thumb piano." The music and dance of the African diaspora, formed to varying degrees on African musical traditions, include American music and many Caribbean genres, such as soca, calypso (see kaiso) and zouk. Latin American music genres such as the rumba, conga, bomba, cumbia, salsa and samba were founded on the music of enslaved Africans, and have in turn influenced African popular music.

Like the music of Asia, India and the Middle East, it is a highly rhythmic music. African music consists of complex rhythmic patterns, often involving one rhythm played against another to create a polyrhythm. The most common polyrhythm plays three beats on top of two, like a triplet played against straight notes. Beyond the rhythmic nature of the music, African music differs from Western music in that the various parts of the music do not necessarily combine in a harmonious fashion. African musicians aim to express life, in all its aspects, through the medium of sound. Each instrument or part may represent a particular aspect of life, or a different character; the through-line of each instrument/part matters more than how the different instruments and parts fit together. African music does not have a written tradition; there is little or no written music to study or analyze. This makes it almost impossible to notate the music – especially the melodies and harmonies – using the Western staff. There are subtle differences in pitch and intonation that do not easily translate to Western notation. African music most closely adheres to Western tetratonic (three-notes), pentatonic (five-note), hexatonic (six-note), and heptatonic (seven-note) scales. Harmonization of the melody is accomplished by singing in parallel thirds, fourths, or fifths. Another distinguishing form of African music is its call-and-response nature: one voice or instrument plays a short melodic phrase, and that phrase is echoed by another voice or instrument. The call-and-response nature extends to the rhythm, where one drum will play a rhythmic pattern, echoed by another drum playing the same pattern. African music is also highly improvised. A core rhythmic pattern is typically played, with drummers then improvising new patterns over the static original patterns.

Music of the Democratic Republic of the Congo varies in its different forms. Outside Africa, most music from the Democratic Republic of Congo is called Soukous, which most accurately refers instead to a dance popular in the late 1960s. The term rumba or rock-rumba is also used generically to refer to Congolese music, though neither is precise nor accurately descriptive.

People from the Congo have no single term for their own music per se, although muziki na biso ("our music") was used until the late 1970s, and now the most common name is ndule, which simply means music in the Lingala language; most songs from the Democratic Republic of the Congo are sung in Lingala.

Since the colonial era, Kinshasa, Congo's capital, has been one of the great centers of musical innovation. The country, however, was carved out from territories controlled by many different ethnic groups, many of which had little in common with each other. Each maintained (and continue to do so) their own folk music traditions, and there was little in the way of a pan-Congolese musical identity until the 1940s.

Like much of Africa, Congo was dominated during the World War II-era by rumba, a fusion of Latin and African musical styles that came from the island of Cuba. Congolese musicians appropriated rumba and adapted its characteristics for their own instruments and tastes. In the 1950s, record labels began appearing, including CEFA, Ngoma, Loningisa and Opika, each issuing many 78 rpm records; Radio Congo Belge also began broadcasting during this period. Bill Alexandre, a Belgian working for CEFA, brought electric guitars to the Congo.

Popular early musicians include Feruzi, who is said to have popularized rumba during the 1930s and guitarists like Zachery Elenga, Antoine Wendo Kolosoy and, most influentially, Jean Bosco Mwenda. Alongside rumba, other imported genres like American swing, French cabaret and Ghanaian highlife were also popular.

In 1953, the Congolese music scene began to differentiate itself with the formation of African Jazz (led by Joseph "Le Grand Kallé" Kabasele), the first full-time orchestra to record and perform, and the debut of fifteen-year-old guitarist François Luambo Makiadi (aka Franco). Both would go on to be some of the earliest Congolese music stars. African Jazz, which included Kabasele, sometimes called the father of modern Congolese music, as well as legendary Cameroonian saxophonist and keyboardist Manu Dibango, has become one of the most well-known groups in Africa, largely due to 1960's "Indépendance Cha Cha", which celebrated Congo's independence and became an anthem for similar movements across the continent.

Into the 1950s, Kinshasa and Brazzaville became culturally linked, and many musicians moved back and forth between them, most importantly Nino Malapet and one of the founders of OK Jazz, Jean Serge Essous. Recording technology had evolved to allow for longer playing times, and the musicians focused on the seben, an instrumental percussion break with a swift tempo that was common in rumba. Both OK Jazz and African Jazz continued performing throughout the decade until African Jazz broke up in the mid-1960s, TPOK Jazz with Franco Luambo Makiadi

at the helm dominated soukous music for the next 20 years.

Tabu Ley Rochereau and Dr. Nico then formed African Fiesta, which incorporated new innovations from throughout Africa as well as American and British soul, rock and country. African Fiesta, however, lasted only two years before disintegrating, and Tabu Ley formed Orchestre Afrisa International instead, but this new group was not able to rival OK Jazz in influence for very long.

Many of the most influential musicians of Congo's history emerged from one or more of these big bands, including the colossus Franco Luambo Makiadi usually referred to simply as "Franco", Sam Mangwana, Ndombe Opetum, Vicky Longomba, Dizzy Madjeku and Kiamanguana Verckys. Mangwana was the most popular of these solo performers, keeping a loyal fanbase even while switching from Vox Africa and Festival des Marquisards to Afrisa, followed by OK Jazz and a return to Africa before setting up a West African group called the African All Stars. Mose Fan Fan of OK Jazz also proved influential, bringing Congolese rumba to East Africa, especially Kenya, after moving there in 1974 with Somo Somo. Rumba also spread through the rest of Africa, with Brazzaville's Pamelo Mounk'a and Tchico Thicaya moving to Abidjan and Ryco Jazz taking the Congolese sound to the French Antilles.

In Congo, students at Gombe High School became entranced with American rock and funk, especially after James Brown visited the country in 1969. Los Nickelos and Thu Zahina emerged from Gombe High, with the former moving to Brussels and the latter, though existing only briefly, becoming legendary for their energetic stage shows that included frenetic, funky drums during the seben and an often psychedelic sound. This period in the late 60s is the soukous era, though the term soukous now has a much broader meaning, and refers to all of the subsequent developments in Congolese music as well.

Stukas and Zaiko Langa Langa were the two most influential bands to emerge from this era, with Zaiko Langa Langa being an important starting ground for musicians like Pepe Feli, Bozi Boziana, Evoloko Jocker and Papa Wemba. A smoother, mellower pop sound developed in the early 1970s, led by Bella Bella, Shama Shama and Lipua Lipua, while Kiamanguana Verckys promoted a rougher garage-like sound that launched the careers of Pepe Kalle and Kanda Bongo Man, among others.

By the beginning of the 1990s, the Congolese popular music scene had declined terribly. Many of the most popular musicians of the classic era had lost their edge or died, and President Mobutu's regime continued to repress indigenous music, reinforcing Paris' status as a center for Congolese music. Pepe Kalle, Kanda Bongo Man and Rigo Starr were all Paris-based and were the most popular Congolese musicians. New genres like madiaba and Tshala Mwana's mutuashi achieved some popularity. Kinshasa still had popular musicians, however, including Bimi Ombale and Dindo Yogo.

In 1993, many of the biggest individuals and bands in Congo's history were brought together for an event that helped to revitalize Congolese music, and also jumpstarted the careers of popular bands like Swede Swede. Another notable feature in Congo culture is its sui generis music. The DRC has blended its ethnic musical sources with Cuban rumba and merengue to give birth to Soukous.

Influential figures of Soukous and its offshoots (N'dombolo, Rumba Rock) are Franco Luambo, Tabu Ley, Simaro Lutumba, Papa Wemba, Koffi Olomide, Kanda Bongo Man, Ray Lema, Mpongo Love, Abeti Masikini, Reddy Amisi, Pepe Kalle, and Nyoka Longo. One of the most talented and respected pioneers of African rhumba - Tabu Ley Pascal Rochereau.

Congolese modern music is also influenced in part by its politics. Zaire, then in 1965, Mobutu Sese Seko took over, and despite massive corruption, desperate economic failure, and the attempted military uprising of 1991, he held on until the eve of his death in 1997, when the president, Laurent Kabila. Kabila inherited a nearly ungovernable shell of a nation. He renamed it the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Kabila could not erase the ruinous effects of the Belgian and Mobutu legacies, and the country is now in a state of chronic civil war. Mobutu instilled a deep fear of dissent and failed to develop his country's vast resources. But the walls he built around his people and his attempts to boost cultural and national pride certainly contributed to the environment that bred Africa's most influential pop music. Call it soukous, rumba, Zairois, Congo music, or kwassa-kwassa, the pop sound emanating from Congo's capital, Kinshasa has shaped modern African culture more profoundly than any other.

Africa produces music genres that are direct derivatives of Congolese Soukous. Some of the African bands sing in Lingala, the main language in the DRC. The same Congolese Soukous, under the guidance of "le sapeur" Papa Wemba, has set the tone for a generation of young guys who dress in expensive designer clothing.The numerous singers and instrumentalists who passed through Zaiko Langa Langa went on to rule Kinshasa's bustling music scene in the '80s with such bands as Choc Stars and Papa Wemba's Viva la Musica.

One erstwhile member of Viva la Musica, Koffi Olomidé, has been indisputably the biggest Zairean/Congolese star since the early '90s. His chief rivals are two veterans of the band Wenge Musica, J.B. Mpiana and Werrason. Mpiana and Werrason each claims to be the originator of ndombolo, a style that intersperses shouts with bursts of vocal melody and harmony over a frenetic din of electric guitars, synthesizers and drums. So pervasive is this style today that even Koffi Olomidé's current repertory is mostly ndombolo.

Currently the Democratic Republic of Congo's music is dominated by the "ndombolo" dance and well represented by the newest congolese superstar:Fally Ipupa is a strong performer from the Democratic Republic of Congo who worked with the legendary Koffi Olomide in his group, Quartier Latin, before branching out on his own. His performances are energetic, his delivery unsurpassable. Female fans love to watch as he whips his songs to new heights in time to his swiveling hips (part of the reason he made the top ten sexiest men list). The mix of rhumba, reggae, soul and ndombolo have proven to be his magical elixir. He has performed to sold out audiences in Paris and New York and continues to gain recognition internationally for his music.

His awards include the Césaire de la Musique award for best male artist of the year (October 2007); he received a gold disc for his album, Droit Chemin, and has been nominated for best music clip, and best artist in the Black Music Awards to be held in Coutonou, Benin on January 12, 2008. Droit Chemin, produced by Maïka Munan (who has worked with famous Congolese musicians such as Tabu Ley Rochereau, M’Bilia Bel, Papa Wemba, Afia Mala), has been received with accolades and is extremely popular with his fans. There other talented artist musicians who emerged after the spit of Wenge Musica known as Ferre Gola, Fabrigas le Mis noir, Awilo Longomba, Cindy le Coeur and more.

There has been a massive movement or a rise of Congolese gospel artists coming out of nowhere. One of them is known as the pioneer of Congolese gospel music, Charles Mombaya who died in May 2007, he had a lot of influences over Congolese gospel music. He managed a small studio " Asifiwe Studio" where he was able to recruit new Congolese talented artists and record them. He recruited hundreds of Congolese singers who became famous including Runo M'vumbi Dembe Moyo, Marie Misamu, Thomas Lokofe, Carlito Lassa, Patrice Ngoy Musoko, Matou Samuel, Lifoko du Ciel, Kool Matope, Couple Buloba, Pepe Kibala, Mopero wa Maloba, Rene Lokua, Mbuta Kamoka, Mimi Mavatiku, Aime Nkanu, Jose Nzita, L'Or Mbongo, Denis Ngonde and more.

Another pillar of Congolese gospel artist whose music revamped worship in the sanctuary in D.R. Congo and worldwide is known as Alain Moloto. His music rich in depth reflective message, poetic and spiritual still impacting the lives of Christian Congolese in Europe, America and African's mostly French-speaking countries. Before his death, his group GAEL split and some of the group members formed a band known as l'Echos d'Adoration with the band leader Franck Mulaja, Henry Papa Mulaja and more. Another family group of Hip pop gospel artist arose from nowhere in the 1990s known as Makoma. Their music influenced a lot of young Africans and impacted lives worldwide.

Now a new generation of gospel artists are taking over Congolese music with amazing talent, sound quality and video clips including; Mike Kalambay, Moise Mbiye, Audit Kabangu and Moise Matuta. A vague of Congolese gospel artist musician are taking over diaspora mostly in the U.S, Canada and Europe. Serayaz is one the group who released their first album in 2017 " Shout of Praise" which can be found on iTunes and other social media platforms. Some of the most famous artists are Melanie Seraya, Steve Mwanza, Kristaal, Dena Mwana and more...

Senegal's music is best known abroad due to the popularity of mbalax, a development of Serer sabar drumming popularized by Youssou N'Dour.

During the colonial ages Senegal was colonized by France and many, though not all, Senegalese identified as French instead of any African ethnicity. Post-independence, the philosophy of negritude arose, which espoused the idea that the griot traditions of Senegal were as valid, classical and meaningful as French classical music. The first President of Senegal, Léopold Sédar Senghor (also a poet) was one of the primary exponents of this.

The national anthem of Senegal, "Pincez tous vos koras, frappez les balafons" ("Pluck all your koras, strike the balafons"), was adopted in 1960. Its lyrics, by president Senghor, refer to the Malian music tradition, while its music was composed by Herbert Pepper (fr).

Ethnically the population of Senegal is 43.3% Wolof, 23.8% Fula, 14.7% Serer, 14.7% Jola, 3% Mandinka and 1.1% Soninka, with 1% European and Lebanese and 9.4% classed as "other" Senegalese music has been influenced by that of the Malian Empire though it tends to be fast and lively whereas the sounds of Malian griots are sedate, classical.

Mbalax (meaning "rhythm" in Wolof),derives its from accompanying rhythms used in sabar music of the Serer people of the Kingdom of Sine and spread to the Kingdom of Saloum whence Wolof migrants brought it to the Wolof kingdoms. The Nder (lead drum), Sabar (rhythm drum), and Tama (talking drum) percussion section traces some of its technique to the ritual music of Njuup. The Serer people infuse their everyday language with complex overlapping cadences and their ritual with intense collaborative layerings of voice and rhythm."

The Njuup was also the progenitor of Tassu, used when chanting ancient religious verses. The griots of Senegambia still use it at marriages, naming ceremonies or when singing the praises of patrons. Most Senegalese and Gambian artists use it in their songs. Each motif has a purpose and is used for different occasions. Individual motifs may represent the history and genealogy of a particular family and are used during weddings, naming ceremonies, funerals etc.

Senegalese popular music can be traced back to the 1960s, when nightclubs hosted dance bands (orchestres) that played Western music. Ibra Kasse's Star Band was the most famous orchestre. After beginning by playing American, Cuban and French songs, Star Band gradually added more indigenous elements, including the talking tama drum and Wolof- or Mandinka-language lyrics. Star Band disintegrated into numerous groups, with Pape Seck's Number One du Senegal being the best known of the next wave of bands, followed by Orchestra Baobab.

The south of Senegal, called Casamance, has a strong Mandinka minority, and began producing masters of the kora in the late 1950s. The band Touré Kunda was the most popular group to arise from this scene, and they soon began playing large concerts across the world.

In 1977, the entire rhythm section and many other performers in the Star Band left to form Étoile de Dakar, who quickly eclipsed their compatriots, and launched the careers of El Hadji Faye and Youssou N'Dour. Faye and N'Dour were Senegal's first pop stars, but the stress of fame soon drove the band apart. Faye and guitarist Badou N'diaye formed Étoile 2000, releasing a hit with "Boubou N'Gary", but soon disappearing from the pop scene.

N'Dour, however, went on to form Super Étoile de Dakar, and his career continued. He was soon by far the most popular performer in the country, and perhaps in all of West Africa. He introduced more traditional elements to his Senegalized Cuban music, including traditional rapping (tassou), njuup, bakou music (a kind of trilling that accompanies Serer wrestling) and instruments like the sabar.

While N'Dour Africanized Cuban music, another influential band, Xalam, was doing the same with American funk and jazz. They formed in 1970, led then by drummer Prosper Niang, but their controversial lyrics and unfamiliar jazz sound led to a lack of popularity, and the group moved to Paris in 1973. There, they added Jean-Philippe Rykiel on keyboards. Xalam toured with groups such as Rolling Stones and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, finally achieving success in Senegal with 1988's Xarit.

In the latter part of the 1970s, the band Super Diamono formed, fusing mbalax rhythms and militant populism with jazz and reggae influences. Their 1982 Jigenu Ndakaru was especially popular. By the middle of the 1980s, Super Diamono was one of the top bands in Senegal, in close and fierce competition with Super Étoile de Dakar. The band's popularity declined, however, slowed somewhat by Omar Pene's reformation in 1991.

This mix is an example of mostly Senegalese music from the 1970s and 1980s but some other African countries are represented as well: https://soundcloud.com/trushmix/trushmix-85-kokk-n-roll

Into the 1990s, Thione Seck, a griot descended from those of Lat Dior, the king of Kayor, arose to solo stardome from Orchestra Baobab, eventually forming his own band called Raam Daan (crawl slowly towards your goal). He used electric instruments on many popular releases, especially Diongoma and Demb. The same period saw the rise of Ismael Lô, a member of Super Diamono, who had major hits, including "Attaya", "Ceddo" and "Jele bi".

Baaba Maal is another popular Senegalese singer. He is from Podor and won a scholarship to study music in Paris. After returning, he studied traditional music with his blind guitarist and family griot, Mansour Seck, and began performing with the band Daande Lenol. His Djam Leelii, recorded in 1984, became a critical sensation in the United Kingdom after it was released there in 1989. Maal's fusions continued into the next decade, with his Firin' in Fouta (1994) album, which used ragga, salsa and Breton harp music to create a popular sound that launched the careers of Positive Black Soul, a group of rappers, and also led to the formation of the Afro-Celt Sound System. His fusion tendencies continued on 1998's Nomad Soul, which featured Brian Eno as one of seven producers.

Though female performers were achieving popular breakthroughs elsewhere in West Africa, especially Mali, Senegalese women had few opportunities before the 1990s. The first international release by a woman was "Cheikh Anta Mbacke" (1989) by Kiné Lam. The song's success led to a string of female performers, including Fatou Guewel, Madiodio Gning, Daro Mbaye and Khar Mbaye Madiaga. Lam, however, remained perhaps the most influential female musician of the 1990s, creating a modernized version of sabar ak xalam ensembles by adding bass guitar and synthesizer with 1993's Sunu Thiossane. The release of Fatou Guewel's CD entitled 'Fatou' in 1998 was significantly influential for Mbalax; this is also the case with her band 'Groupe Sope Noreyni'.

The new century has seen the rise of Viviane Ndour, who got her first break as a backing vocalist to Youssou Ndour with Super Etoile. She is well known in Senegal and the diaspora, collaborating with French rap star Mokobe and Zouk artist Philip Montiero and incorporating RnB, Hip-Hop and other elements into her own style of Mbalax.

Acoustic folk music has also left its mark on Senegal's music culture. Artists that have contributed to this genre include TAMA from Rufisque, Pape Armand Boye, les Freres Guisse, Pape et Cheikh, and Cheikh Lo.

The biggest trend in 1990s Senegal, however, was hip hop. Traditional culture includes rapping traditions, such as the formal tassou, performed by women of the Laobe woodworking class the morning after marriages. Modern Senegalese hip hop is mostly in Wolof, alongside some English and French. Positive Black Soul is the best-known group in the country, Daara j, Gokh-Bi System and Wageble too. Senegalese-French rapper MC Solaar is a very well known musician. Senegalese born Akon has risen to world fame.

In 2008 English musician Ramon Goose travelled to Dakar and collaborated with Senegalese griot Diabel Cissokho to record the album Mansana Blues which explores African blues & traditional West African styles, this led on to the formation of The West African Blues Project.

The music of the Gambia is closely linked musically with that of its neighbor, Senegal, which surrounds its inland frontiers completely. Among its prominent musicians is Foday Musa Suso. Mbalax is a widely known popular dance music of the Gambia and neighbouring Senegal. It fuses popular Western music and dance, with sabar, the traditional drumming and dance music of the Wolof and Serer people.

"For The Gambia Our Homeland", the national anthem of the Gambia, was composed by Jeremy Frederic Howe, based on the traditional Mandinka song "Foday Kaba Dumbuya", with words by Virginia Julia Howe, for an international competition to produce an anthem (and flag) before independence from the United Kingdom in 1965.

The Gambia, the smallest country in mainland Africa, is an independent coastal state along the River Gambia. It gained its separate identity as a colony of the United Kingdom while Senegal was a colony of France, but the two countries' traditional music are very much intertwined. Among Gambia's people, who together number some 1.728 million (2010), 42% are Mandinka, 18% Fula, 16% Wolof\Serer, 10% Jola and 9% Soninke, the remainder being 4% other African and 1% non-African (2003). 63% of Gambians live in rural villages (1993 census), though the population is young and tends towards urbanization. 90% are Muslims and most of the remainder Christians.

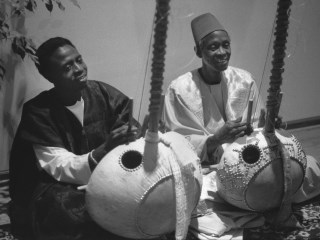

Griots, also known as jelis, hereditary praise-singers, a legacy of the Mande Empire, are common throughout the region. Gambian griots, as elsewhere, often play the kora, a 21 string harp. The region of Brikama has produced some famous musicians, including Foday Musa Suso, who founded the Mandingo Griot Society in New York City in the 1970s, bringing Mande music to the New York avant-garde scene and collaborating with Bill Laswell, Philip Glass and the Kronos Quartet.

Mbalax (meaning "rhythm" in Wolof), derives its from accompanying rhythms used in sabar, a tradition that originated from the Serer of the Kingdom of Sine and spread to the Kingdom of Saloum whence Wolof migrants took it to the Wolof kingdoms. The Nder (lead drum), Sabar (rhythm drum), and Tama (talking drum) percussion section traces some of its technique to the ritual music of Njuup.

The Njuup was also progenitor of Tassu, used when chanting ancient religious verses. The griots of Senegambia still use it at marriages, naming ceremonies or when singing the praises of patrons. Most Senegalese and Gambian artists use it in their songs. The Serer people are known especially for vocal and rhythmic practices that infuse their everyday language with complex overlapping cadences and their ritual with intense collaborative layerings of voice and rhythm." Each motif has a purpose and is used for different occasions. Individual motifs represent the history and genealogy of a particular family and are used during weddings, naming ceremonies, funerals etc.

Gambian popular music began in the 1960s. The Super Eagles and Guelewar formed under the influence of American, British and Cuban music. The Super Eagles played merengue and other pop genres with Wolof lyrics and minor African elements. They visited London in 1977, appearing on Mike Raven's Band Call. After the programme, when the band began playing traditional tunes, an unknown listener is said to have inspired the group to return to the Gambia's musical roots, and they spent two years travelling around studying traditional music. The reformed band was called Ifang Bondi, and their style was Afro-Manding blues.

Gambian Laba Sosseh, who relocated to Dakar, Senegal as a teenager, spent his entire career outside of the Gambia, becoming a significant presence in the African and New York salsa scene. Civil unrest caused Ifang Bondi and other Gambian musicians to leave for Europe.

Former Ifang Bondi musician Juldeh Camara has been working with Justin Adams since 2007 and has been touring all over the world. Also from Ifang Bondi, Musa Mboob and Ousman Beyai have started a new group XamXam which started with a project in the Gambia to produce new music by taking six musicians based in the UK to the Gambia to work with top musicians from four different tribal backgrounds. Ousman Beyai moved to the UK where he worked with Musa Mboob to set up the live band XamXam.

Jaliba Kuyateh and his Kumareh band is currently the most popular exponent of Gambia's Mandinka music. There is also a thriving Gambian hip hop scene.

The Music of Mali is, like that of most African nations, ethnically diverse, but one influence predominates; that of the ancient Mali Empire of the Mandinka (from c. 1230 to c. 1600). Mande people (Bambara, Maninke, Soninke) make up 50% of the country's population, other ethnic groups include the Fula (17%), Gur-speakers 12%, Songhai people (6%), Tuareg and Moors (10%) and another 5%, including Europeans. Mali is divided into eight regions; Gao, Kayes, Koulikoro, Mopti, Ségou, Sikasso, Tombouctou and Bamako (the eighth region, Kidal, was created in 1991).

Salif Keita, a noble-born Malian who became a singer, brought Mande-based Afro-pop to the world, adopting traditional garb and styles. He says he sings to express himself, however, and not as a traditional jeli or praise-singer. The kora players Sidiki Diabaté and Toumani Diabaté have also achieved some international prominence as have the late Songhai/Fula guitarist Ali Farka Touré and his successors Afel Bocoum and Vieux Farka Touré, the Tuareg band Tinariwen, the duo Amadou et Mariam and Oumou Sangare. Mory Kanté saw major mainstream success with techno-influenced Mande music.

While internationally Malian popular music has been known more for its male artists, domestically, since at least the 1980s, female singers such as Kandia Kouyaté are ubiquitous on radio and television, in markets and on street-corner stalls. Fans follow them for the moralizing nature of their lyrics, the perception that they embody tradition and their role as fashion trend-setters.

The national anthem of Mali is "Le Mali". After independence under President Modibo Keita orchestras were state-sponsored and the government created regional orchestras for all seven then regions. From 1962 the orchestras competed in the annual "Semaines Nationale de la Jeunesse" ("National Youth Weeks") held in Bamako. Keita was ousted by a coup d'état in 1968 organized by General Moussa Traoré.

Most of Keita's support for the arts was cancelled, but the "Semaines Nationale de la Jeunesse" festival, renamed the "Biennale Artistique et Culturelle de la Jeunesse", was held every 2 years starting in 1970. Notable and influential bands from the period included the first electric dance band, Orchestre Nationale A, and the Ensemble Instrumental National du Mali, comprising 40 traditional musicians from around the country and still in operation today.

Mali's second president, Moussa Traoré, discouraged Cuban music in favor of Malian traditional music. The annual arts festivals were held biannually and were known as the Biennales. At the end of the 1980s public support for the Malian government declined and praise-singing's support for the status quo and its political leaders became unfashionable. The ethnomusicologist Ryan Skinner has done work on the relationship of music and politics in contemporary Mali.

The Malinké, Soninke - Sarakole, Dyula and Bambara peoples form the core of Malian culture, but the region of the Mali Empire has been extended far to the north in present-day Mali, where Tuareg and Maure peoples continue a largely nomadic desert culture. In the east Songhay, Bozo and Dogon people predominate, while the Fula people, formerly nomadic cattle-herders, have settled in patches across the nation and are now as often village and city dwelling, as they are over much of West Africa.

Historical interethnic relations were facilitated by the Niger River and the country's vast savannahs. The Bambara, Malinké, Sarakole, Dogon and Songhay are traditionally farmers, the Fula, Maur, and Tuareg herders and the Bozo are fishers. In recent years, this linkage has shifted considerably, as ethnic groups seek diverse, nontraditional sources of income.

Mali's literary tradition is largely oral, mediated by jalis reciting or singing histories and stories from memory. Amadou Hampâté Bâ, Mali's best-known historian, spent much of his life recording the oral traditions of his own Fula teachers as well as those of Bambara and other Mande neighbors. The jeliw (sing. jeli, fem. jelimusow, French griot) are a caste of professional musicians and orators, sponsored by noble patrons of the horon class and part of the same caste as craftsmen (nyamakala).

They recount genealogical information and family events, laud the deeds of their patron's ancestors and praise their patrons themselves, as well as exhorting them to behave morally to ensure the honour of the family name. They also act as dispute mediators. Their position is highly respected and they are often trusted by their patrons with privileged information since the caste system does not allow them to rival nobles. The jeli class is endogamous, so certain surnames are held only by jeliw: these include Kouyaté, Kamissoko, Sissokho, Soumano, Diabaté and Koné.

Their repertoire includes several ancient songs of which the oldest may be "Lambang", which praises music. Other songs praise ancient kings and heroes, especially Sunjata Keita ("Sunjata") and Tutu Jara ("Tut Jara"). Lyrics are composed of a scripted refrain (donkili) and an improvised section. Improvised lyrics praise ancestors, and are usually based around a surname. Each surname has an epithet used to glorify its ancient holders, and singers also praise recent and still-living family members. Proverbs are another major component of traditional songs.

These are typically accompanied by a full dance band The common instruments of the Maninka jeli ensemble are;

The Mande people, including the Mandinka, Maninka and Bamana, have produced a vibrant popular music scene alongside traditional folk music and that of professional performers called jeliw (sing. jeli, French griot) The Mande people all claim descent from the legendary warrior Sunjata Keita, who founded the Mande Empire. The language of the Mande is spoken with different dialects in Mali and in parts of surrounding Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Senegal and The Gambia.

The kora is by far the most popular traditional instrument. It is similar to both a harp and a lute and can have between 21 and 25 strings. There are two styles of playing the kora; the western style is found mostly in Senegal and The Gambia, and is more rhythmically complex than the eastern tradition, which is more vocally dominated and found throughout Mali and Guinea. Ngoni (lutes) and balafon (xylophones) are also common.

Mande percussion instruments include the tama, djembe and dunun drums. Jeli Lamine Soumano states: "If you want to learn the bala go to Guinea or Mali. If you want to learn the kora go to Gambia or Mali. If you want to learn the n'goni you have only to go to Mali." Each area has developed a speciality instrument while still recognizing that the roots of the related forms come from Mali.

The traditional djembe ensemble is most commonly attributed to the Maninka and Maraka: it basically consists of one small dunun (or konkoni) and one djembe soloist. A djembe accompanist who carries a steady pattern throughout the piece has since been added, as have the jeli dununba (also referred to as the kassonke dunun, names derived from the style of playing, not the physical instruments), and the n'tamani (small talking drum). Many ethnic groups, including the Kassonke, the Djokarame, the Kakalo, the Bobo, the Djoula, the Susu, and others, have historical connections with the djembe.

Most vocalists are female in everyday Mande culture, partially due to the fact that many traditional celebrations revolve around weddings and baptisms, mostly attended by women. Several male and female singers are world-renowned. Although it once was rare for women to play certain instruments, in the 21st century women have broadened their range.

Bamana-speaking peoples live in central Mali: the language is the most common in Mali. Music is simple and unadorned, and pentatonic. Traditional Bamana music is based on fileh (half calabash hand drum), gita (calabash bowl with seeds or cowrie shells attached to sound when rotated),the karignyen (metal scraper), the bonkolo drum (played with one open hand and a thin bamboo stick), the kunanfa (large bowl drum with cowhide head, played with the open hands, also barra or chun), the gangan (small, mallet-struck dunun, essentially the same as the konkoni or kenkeni played in the djembe ensemble).

The melodic instruments of the Bamana are typically built around a pentatonic structure. The slat idiophone bala, the 6-string doson n'goni (hunter's lute-harp) and its popular version the 6-12 string kamel n'goni, the soku (gourd/lizard skin/horse hair violin adopted from the Songhai, soku literally means "horse tail"), and the modern guitar are all instruments commonly found in the Bamana repertoire. Bamana culture is centered around Segou, Sikasso, the Wassalou region and eastern Senegal near the border of Mali's Kayes region.

Well-known Bamana performers include Mali's first female musical celebrity, Fanta Damba. Damba and other Bamana (and Maninka) musicians in cities like Bamako are known throughout the country for a style of guitar music called Bajourou (named after an 18th-century song glorifying ancient king Tutu Jara). Bamana djembe ("djembe" is a French approximation of the Maninka word, with correct English phonetic approximation: jenbe) drumming has become popular since the mid-1990s throughout the world. It is a traditional instrument of the Bamana people from Mali (This is incorrect, the instrument is a Maninka/Maraka instrument adopted by the Bamana).

The Mandinka live in Mali, The Gambia and Senegal and their music is influenced by their neighbors, especially the Wolof and Jola, two of the largest ethnic groups in the Senegambian region. The kora is the most popular instrument.

Maninka music is the most complex of the three Mande cultures. It is highly ornamented and heptatonic, dominated by female vocalists and dance-oriented rhythms. The ngoni lute is the most popular traditional instrument. Most of the best-known Maninka musicians are from eastern Guinea and play a type of guitar music that adapts balafon-playing (traditional xylophone) to the imported instrument.

Maninka music traces its legend back more than eight centuries to the time of Mansa Sunjata. In the time of Mali Empire and his semi-mythic rivalry with the great sorcerer-ruler Soumaoro Kante Mansa of the Susu people, Sunjata sent his jeli Diakouma Doua to learn the secrets of his rival. He finds a magical balafon, the "Soso Bala", the source of Soumaoro's power. When Soumaoro heard Diakouma Doua play on the bala he named him Bala Fasseke Kwate (Master of the bala). The Soso Bala still rests with the descendants of the Kouyate lineage in Niaggasola, Guinea, just across the modern border from Mali.

Tinariwen is thought to be the first Tuareg electric band, active since 1982. They played at the Eden project stage of the Live8 concert in July 2005.

The Fula use drums, the hoddu (same as the xalam, a plucked skin-covered lute similar to the banjo) and the riti or riiti (a one-string bowed instrument, in addition to vocal music. "Zaghareet" or ululation is a popular form of vocal music formed by rapidly moving the tongue sideways and making a sharp, high sound.

The Mansa Sunjata forced some Fulani to settle in various regions where the dominant ethnic groups were Maninka or Bamana. Thus, today, we see a number of people with Fula names (Diallo, Diakite, Sangare, Sidibe) who display Fula cultural characteristics, but only speak the language of the Maninka or Bamana.

The Songhay are not an ethnic or a linguistic group but one that traces its history to the Songhai Empire and inhabits the great bend of the mid River Niger. Vieux Farka Toure, son of Ali Farka Toure, has gained popularity after playing in front of an estimated 1 billion viewers worldwide at the 2010 FIFA World Cup in South Africa. He has also been called, "the Hendrix of the Sahara", since his music explores the affinity between West African song and Afro-American blues guitar.

After World War 2 the guitar became common throughout Africa, partially resulting from the mixing of African, American and British soldiers. Dance bands were popular in Mali, especially the town of Kita's orchestra led by Boureima Keita and Afro-Jazz de Ségou, the Rail Band and Pioneer Jazz. Imported dances were popular, especially rumbas, waltzes and Argentine-derived tangos. By the 1960s, however, the influence of Cuban music began to rise. After independence in 1960, Malians saw new opportunities for cultural expression in radio, television and recordings. Cuban music remained popular in Mali throughout the 1960s and remains popular today.

Old dance bands reformed under new names as part of the roots revival of Moussa Traoré. Especially influential bands included Tidiane Koné's Rail Band du Buffet Hôtel de la Gare, which launched the careers of future stars Salif Keita and Mory Kanté, and Super Biton de Ségou. Bajourou also became popular, beginning with Fanta Sacko's Fanta Sacko, the first bajourou LP. Fanta Sacko's success set the stage for future jelimusow stars which have been consistently popular in Mali; the mainstream acceptance of female singers is unusual in West Africa, and marks Malian music as unique. In 1975, Fanta Damba became the first jelimuso to tour Europe, as bajourou continued to become mainstream throughout Mali.

Not all bands took part in Traoré's roots revival. Les Ambassadeurs du Motel formed in 1971, playing popular songs imported from Senegal, Cuba and France. Les Ambassadeurs and Rail Band were the two biggest bands in the country, and a fierce rivalry developed. Salif Keita, perhaps the most popular singer of the time, defected to Les Ambassadeurs in 1972. This was followed by a major concert at which both bands performed as part of the Kibaru (literacy) program. The audience fell into a frenzy of excitement and unity, and the concert is still remembered as one of the defining moments in 1970s Malian music.

The mid-70s also saw the formation of National Badema, a band that played Cuban music and soon added Kasse Mady Diabaté who led a movement to incorporate Maninka praise-singing into Cuban-style music.

Both the Rail Band and Les Ambassadeurs left for Abidjan at the end of the 1970s due to a poor economic climate in Mali. There, Les Ambassadeurs recorded Mandjou, an album which featured their most popular song, "Mandjou". The song helped make Salif Keita a solo star. Many of the biggest musicians of the period also emigrated—to Abidjan, Dakar, Paris (Salif Keita, Mory Kanté), London, New York or Chicago. Their recordings remained widely available, and these exiles helped bring international attention to Mande music.

Les Ambassadeurs and Rail Band continued recording and performing under a variety of names. In 1982 Salif Keita, who had recorded with Les Ambassadeurs' Kanté Manfila, left the band and recorded an influential fusion album, Soro, with Ibrahima Sylla and French keyboardist Jean-Philippe Rykiel. The album revolutionized Malian pop, eliminating all Cuban traces and incorporating influences from rock and pop. By the middle of the decade, Paris had become the new capital of Mande dance music. Mory Kanté saw major mainstream success with techno-influenced Mande music, becoming a #1 hit on several European charts.

Another roots revival began in the mid-1980s. Guinean singer and kora player Jali Musa Jawara's 1983 Yasimika is said to have begun this trend, followed by a series of acoustic releases from Kanté Manfila and Kasse Mady. Ali Farka Touré also gained international popularity during this period; his music is less in the jeli tradition and resembles American blues.

The region of Wassoulou, south of Bamako, became the centre of a new wave of dance music also referred to as wassoulou. Wassoulou had been developing since at least the mid-70s. Jeliw had never played a large part in the music scene there, and music was more democratic.

The modern form of wassoulou is a combination of hunter's songs with sogoninkun, a type of elaborate masked dance, and the music is largely based on the kamalengoni harp invented in the late 1950s by Allata Brulaye Sidibí. Most singers are women. Oumou Sangaré was the first major wassoulou star; she achieved fame suddenly in 1989 with the release of Moussoulou, both within Mali and internationally. Wasulu region of southwest Mali. The soku is a traditional Wassoulou single string fiddle, corresponding to the Songhai n'diaraka or njarka, that doubles the vocal melody.

Since the 1990s, although the majority of Malian popular singers are still jelimusow, wassoulou's popularity has continued to grow. Wassoulou music is especially popular among youth. Although western audiences categorise wassoulou performers like Oumou Sangaré as feminists for criticizing practices like polygamy and arranged marriage, within Mali they are not viewed in that light because their messages, when they do not support the status quo of gender roles, are subtly expressed and ambiguously worded, thus keeping them open to a variety of interpretations and avoiding direct censure from Malian society.

Text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License.

Date: February 2020.

Photo Credits:

(1),(15) Staff Benda Bilili,

(2)-(5) Afro-Pfingsten Winterthur 2017 & 2018,

(6) Kanda Bongo Man,

(7) Les Tambours de Brazza,

(8) 'Kinshasa 1978',

(9) Konono N°1,

(10) Niasony,

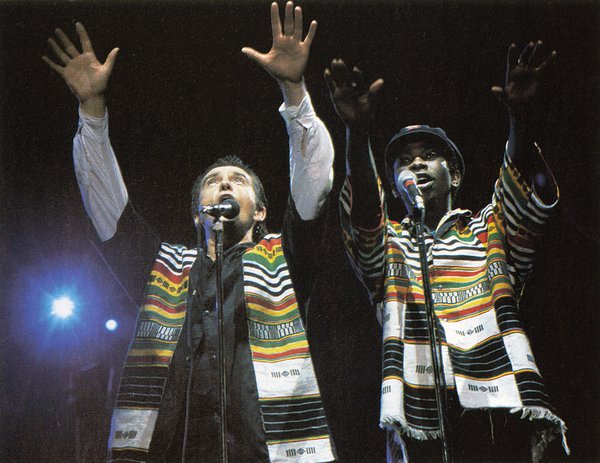

(11)-(12) Zap Mama,

(13) Kitio,

(14) 'Putumayo Presents: Congo to Cuba',

(16) Peter Gabriel & Youssou N’Dour,

(17) Ablaye Cissoko,

(18)-(19) Baye Magatte,

(20) Cheikh Lô,

(21) Pascal Bokar 'American Trails',

(22) Awale Jant Band 'YEWOULEN',

(23)-(24) Ibrahima Cissokho,

(25) Soulsha,

(26) 'The Rough Guide to the Music of Senegal',

(27) Baaba Maal,

(28) Nuru Kane,

(29) Awa Ly,

(30) Marema,

(31) Lao Kouyate,

(32) Positive Bayefall,

(33)-(34) 'Gambian Griot Kora Duets',

(35) Foday Musa Suso,

(36) 'The Gambia Sessions',

(37) Sona Jobarteh,

(38) 'The Gambia: Tata Dindin. Salam - New Kora Music',

(39) Jaaleekaay,

(40) Musa Mboob,

(41) 'Tuareg Music of the Southern Sahara',

(42) Fatoumata Diawara,

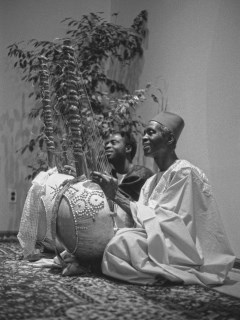

(43)-(44) Bassekou Kouyate & Ngoni Ba 'Miri',

(45) Alba Griot,

(46) 'Sissoko & Sissoko',

(47) 3ma (ft. Ballaké Sissoko),

(48) Invisible System 'Dance to the Full Moon',

(49) Trio Da Kali,

(50) 'Putumayo Presents: Mali',

(51) Habib Koité,

(52) Tartit,

(53) Djely Tapa,

(54) Boubacar Traoré,

(55) Abou Diarra,

(56) Vieux Farka Touré,

(57) Samba Touré

(unknown/website);

(58) Tinariwen,

(59) Tamikrest

(by Walkin' Tom).