Folk & The City: Madrid (1)

Folk & The City: Madrid (1) |

The ‘Early’ Folk Musicians

Folk & The City: Madrid, Spain (Part 2)

The first Folk & The City article on Madrid pointed out bars and pubs where you can listen to traditional and folk music live in concert today. This second article will recognize and put in context key musicians which pioneered the concept of folk music as we know it today way back in the thorny 1960s and '70s, rooted in ancient traditions of Spanish folklore.

|

|

As explained in past Folk World articles, Flamenco has been the most successful type of Spanish traditional music, and its capacity to get melodies and rhythms blended in the sounds of several mainstream Spanish bands (rock, blues, pop, jazz,…) along the last decades, is significant : Medina Azahara, Triana, Pata Negra, Ketama, Raimundo Amador, Kiko Veneno, Jorge Pardo, Lagartija Nick, Chambao, Ojos de Brujo, Los Delinqüentes,… . But this is not really what should be considered Spanish folk, or probably not always ‘new flamenco’… although you could easily listen to this sort of music when you tune in a radio station in Madrid or in most other places in Spain.

Folk music in Spain lives in its own bucolic & ‘outmoded’ planet, in someway modestly aside from the rest of the music market (including flamenco), and fairly… not for a majority of Spanish people. Nonetheless, let’s say that every ten or twenty years, some of the big managers of the pop music business in Madrid or Barcelona seem to re-incorporate forgotten flavors in their marketing campaigns. That gives a chance to some of our top folk musicians to somehow experience the life of the rock and pop stars. That was the case in the 90s for folk music artists such as: Celtas Cortos, Luar Na Lubre, Carlos Núñez, Kepa Junquera, Hevia, Cristina Pato, Ixo Rai,…

That kind of Spanish folk musicians have usually fused their deep knowledge of old traditional sounds from different places, with influences from pop or R&R music, or even Irish, British, North American, Caribbean or Scandinavian folk :

So as you can see, the Spanish traditional & folk musicians that have recently enjoyed widespread popularity at national level, seem to be mostly from the South, with some kind of flamenco essences, or from the North, bringing their cheerful or gentle ‘Celtic’ sounds, whatever that means: bagpipes, accordions, fiddles,…

|

|

Folk music as we know it today, became noteworthy in Spain in the late 1960’s & the 70’s. Before then, traditional music was mostly part of the local folklore of most rural areas, many times simply as it had been carried generation after generation for the last centuries. Industrialization was still arriving late to most Spanish villages and towns in the second half of the twentieth century. However, it was becoming evident that the accelerating immigration of people from the countryside towards the big cities and other countries (France, Germany, UK, Belgium,..), could precede to the final extinction of many ancient traditions. That pushed several young Spanish musicians to play an active role in the study and continuation of the popular traditions, as musicologists and folklorists from previous generations had been doing in different parts of Spain (Manuel Garcia-Matos in Extremadura, Agapito Marazuela in Castile, Jesús Bal y Gay in Galicia, Eduardo Martinez–Torner in Asturias, …).

It is also important to keep in mind that in those days and until 1976, Spain was ruled by the nationalist dictatorship from general Francisco Franco, who began the civil war in 1936, which ended in 1939. Franco’s army started & won the Spanish civil war as an anti-republican and anti-communist rebellion, also supported by weapons and troops from Hitler and Mussolini. During Franco’s regime, the different Spanish musical folklore and traditions became an instrument used by some government organizations, to strengthen knowledge and pride on the Spanish national identity. Even more, certain displays of ‘peripheral’ regional traditions (Galician, Basque, Catalonian,…) were tolerated as means to manifest the diversity of the country’s culture, and as long as their performers also proved loyalty to the ideal of a unified and catholic Spain. After the 50s and 60s, this care for the national folklore was probably also naively considered a way to counterbalance the boosting and ‘dangerously anarchic’ influence on the Spanish youth of foreign idols, such as: Elvis Presley, The Beatles, Bob Dylan, The Rolling Stones, etc…

|

|

Madrid has been Spain’s center of political power for centuries, and as such, it has always attracted people from all parts of the country : students, factory workers, managers, politicians, scientists, engineers, artists,…. There were several folk musicians that became popular in Madrid in those 1960s and 70s, although in many cases they were originally from other provinces of the regions around Spain’s capital. They are listed next in two categories :

|

Singers Inspired by Trad & Folk Music

There was a significant number of folk singers that developed their career in the 60s and 70s in Madrid, although in Spain they are normally considered under the category of “cantautores” ( author-singers, song writers ), and not so much as folk musicians. This means that even though in many cases their music is clearly inspired by traditional Spanish songs, their compositions are mainly in a more personal and creative style, with influences that can range from Georges Brassens and Bob Dylan, to South-American or African folk musicians, flamenco, classical, Sepharadic or medieval music, rock, blues, jazz,…

One of the common traits of these singers is that during the 60s, and mostly the 70s, their songs were heartily implicated in Spain’s political situation, containing messages demanding freedom and the end of Franco’s dictatorship, or with references to texts from writers, poets, singers,… which were considered subversive by the government and the police at that time. Many protest songs were forbidden by the censorship committees. Their lyrics were deemed as containing dangerous messages for the catholic moral or the ideological foundations of Franco’s regime. The authors and singers of such songs were even arrested and punished sometimes. In these regards, it deserves a special mention the group of Spanish folk singers named ‘Canción del Pueblo’ ( Song of the People ), that in 1967-68 raised their voices in Madrid.

The following list summarizes the main ‘cantautores’ that started their career in those decades in Madrid.

|

He was born in Zamora in 1947, and in the mid 1960s he started deeply studying, playing and teaching the Castilian and Spanish-Jewish (Sepharadic) folklore in Valladolid (both cities are in the Castilla y León community). He published his first album in 1967, ‘Recital’ (edited by Movieplay) and the last one in 2005, ‘Dendrolatrías’ (Factoría Autor). In total he has published around 30 albums, 50 books and around 200 articles and essays, plus TV programs, conferences in universities in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Germany, Holland and the USA. Joaquín Diaz has been very influential for the rest of Castilian folk musicians including those in Madrid. He stopped giving concerts in 1976 to concentrate his efforts on the research of the popular culture and traditions, and finally to establish a foundation and museum for the Castilian tradition in the village of Urueña (Valladolid province). Joaquin is the uncle of the zanfona (hurdy gurdy) player

Germán DÍAZ.

He was born in Zamora in 1947, and in the mid 1960s he started deeply studying, playing and teaching the Castilian and Spanish-Jewish (Sepharadic) folklore in Valladolid (both cities are in the Castilla y León community). He published his first album in 1967, ‘Recital’ (edited by Movieplay) and the last one in 2005, ‘Dendrolatrías’ (Factoría Autor). In total he has published around 30 albums, 50 books and around 200 articles and essays, plus TV programs, conferences in universities in Spain, Portugal, France, Italy, Germany, Holland and the USA. Joaquín Diaz has been very influential for the rest of Castilian folk musicians including those in Madrid. He stopped giving concerts in 1976 to concentrate his efforts on the research of the popular culture and traditions, and finally to establish a foundation and museum for the Castilian tradition in the village of Urueña (Valladolid province). Joaquin is the uncle of the zanfona (hurdy gurdy) player

Germán DÍAZ.

NUESTRO PEQUEÑO MUNDO (NPM) (“Our Small World”)

|

|

Born and raised in a village in Segovia (province of Castilla-León, at the north of Madrid), he moved to Paris in 1960, where he played as a young professional guitarist. At that time, South American folk and flamenco music were highly fashionable styles, but Ismael understood that he could also succeed incorporating songs from the traditional Spanish repertoire. He studied and played the guitar songs from the Spanish composers of the 15th and 16th centuries, until he published a record ‘Canciones del Pueblo, Canciones del Rey’ which was awarded with the Grand Prix du Disque. After traveling throughout Europe, he developed an increasing interest in the study and recollection of popular traditions and folklore, and when he came back to Spain in the late 60s, he intensely continued such activities. In the early 70s, he hosted a program in the Spanish national TV where he explained to the children different aspects of the Spanish folklore. Nowadays, he keeps one of the largest collections in Spain on traditional instruments, and not just musical, but also farming tools, clothes, pottery,…

Born and raised in a village in Segovia (province of Castilla-León, at the north of Madrid), he moved to Paris in 1960, where he played as a young professional guitarist. At that time, South American folk and flamenco music were highly fashionable styles, but Ismael understood that he could also succeed incorporating songs from the traditional Spanish repertoire. He studied and played the guitar songs from the Spanish composers of the 15th and 16th centuries, until he published a record ‘Canciones del Pueblo, Canciones del Rey’ which was awarded with the Grand Prix du Disque. After traveling throughout Europe, he developed an increasing interest in the study and recollection of popular traditions and folklore, and when he came back to Spain in the late 60s, he intensely continued such activities. In the early 70s, he hosted a program in the Spanish national TV where he explained to the children different aspects of the Spanish folklore. Nowadays, he keeps one of the largest collections in Spain on traditional instruments, and not just musical, but also farming tools, clothes, pottery,…

NUEVO MESTER DE JUGLARÍA (a.k.a. ‘El Mester’)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The next article on Madrid will talk about the following generation of folk musicians, those that appeared in Madrid in the 1980s, '90s and… My gratitude to the Spanish music magazine INTERFOLK (www.inter-folk.net), and in particular Fernando MARTÍNEZ–GARCIA, for the ex-pert support for this article. |

Photo Credits:

(1) Plaza Mayor, Madrid;

(2) Raimundo Amador;

(3) Celtas Cortos;

(4) Psaltery and flute player, Yebra de Basa;

(5) Paco Ibanez;

(6) Joaquin Diaz Gonzalez;

(7) Chicho Sanchez-Ferlosio;

(8) Nuestro Pequeno Mundo;

(9) Ismael Pena;

(10) Nuevo Mester de Juglaria;

(11) Pablo Guerrero;

(12) Eliseo Parra;

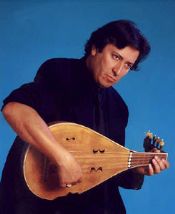

(13) Luis Delgado;

(14) Raices;

(15) Julia Leon.

|

To the German FolkWorld |

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 11/2009

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.