Alison Tokita & David W. Hu-ghes (eds.), The Ashgate Re-search Companion to Japa-nese Music. Ashgate Publi-shing, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7546-5699-9, 446pp, £65.00 (incl. CD).

FolkWorld Issue 38 03/2009; Book Reviews by Walkin' T:-)M

Let me start with something that was absolutely new to me and, I suppose, to most FolkWorld readers alike: Japanese Music! However, this is only the beginning of a literature trip around the globe.

The Japanese introduced Western music into their education system in the 19th century, when Japan's isolation was forcibly ended by gunboat diplomacy, also leading to Western musical hegemony. Thus most Japanese today are more familiar with yogaku (i.e. Western or westernized music) than with hogaku (national music), not to mention minzoku ongaku (folkloric music). Japan invented several educational methodologies (Yamaha music schools, Suzuki method) and did become a world leader in the mass production of Western musical instruments and technology (mp3 players, walkmen, synthesizers). But where's Japanese music?

Virtually all traditional Japanese instruments were introduced from China in the 6th to 9th century. The Japanese also imported gagaku (court music), the world's oldest continually performed orchestral music, and shomyo (Buddhist vocal music). The Middle Ages brought

Alison Tokita & David W. Hu-ghes (eds.), The Ashgate Re-search Companion to Japa-nese Music. Ashgate Publi-shing, 2008, ISBN 978-0-7546-5699-9, 446pp, £65.00 (incl. CD). |

Peasant's music included work songs, dance songs, songs for relaxation and festivities. Genres and lyrics were not significantly different in nature from those of the West. Instrumental accompaniment was not necessary; drums and shakuhachi (bamboo flute) were common, sometimes a shamisen. The music was overwhelmingly monophonic, based on a pentatonic scale with three-note tetrachords. Duple metres (including 6/8) were common, and virtually no triple metre. Improvisation was nearly absent.

When the new word min'yo - literally folk song - began to gain currency in Japan in the early twentieth century, many people were slow to grasp its intent. When a min'yo concert was advertised in Tokyo in 1920, some people bought tickets expecting to hear the music of the no theatre; others, notably the police, took the element min- in the sense given by the left-wing movement, anticipating a rally singing people's songs. The modern concept of 'the folk' springs from the German Romantics. The term Volkslied coined by Herder in 1775, appeared in English as 'folk song' in the mid-1800s and reached Japan by around 1890 as min'yo (with the attendant intellectual bagagge of Romanticism).During time min'yo was more often heard in the cities than in the countryside. It became a kind of classical music whose primary function was entertainment. Folk singer became a profession. In the 1960s, the American urban folk movement reached Japanese universities. Hootenannies and jamborees were held on many campuses. Young musicians covered American singer-songwriters and developed a style called foku songu, humourous and ironic, sometimes protesting Japanese songs accompanied by instruments such as banjo and guitar.

The latest folk craze was in the late 1970s, introducing shin-min'yo (new folk songs) with pentatonic major and minor modes, thus allowing Western-style harmonization and world-embracing modernistic lyrics. A few singers, Ito Takio or Chanchiki, have incorporated jazz and rock music into their min'yo fusion. Okinawan folk music finds great resonance, its predominant mode resembling a slightly simplified Western major mode. Large ensembles centred on stick-drums, the most famous is the group Kodo (-> FW#37), are quite popular. Kano Oki (-> FW#34) of the indigenous Ainu people brought the tonkori zither onto the world's music stages.

The Ashgate Research Companion to Japanese Music covers all periods and genres in great detail, and is much more than an overview. (Besides, it challenges the myth that Japanese of all people in the world use the left brain to perceive music.) I wished some things would have been better explained; a glossary of Japanese terms would have been helpful at times (it was intended to make an on-line index available). But if you absorb the collected knowledge of this volume, you probably know more about the subject than the average Japanese.

There are many music samples. Eventually an extensive bibliography (featuring enough works in western languages) is given, and an audio/videography (featuring mostly CDs, some LPS, cassette tapes, VHS videos, 16 mm films, but only a few DVDs). The book's accompanying CD features short excerpts, including folk music. What caught my attention was a rice-transplanting song, where the women plant the seedlings and sing the chorus and the men provide the lead vocal and accompaniment on drums, flutes and cymbals. You can see another example at the end of "The Seven Samurai" film.

The Japanese craze for karaoke entertainment has made an impact throughout the world. Vice versa,

Helen O'Shea, The Making of Irish Traditional Music. Cork University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-185918-436-3, 224pp, €39. |

Enda Scahill's Irish Banjo Tutor. www.endascahill.com, 2008, ISBN 978-0-955345623, 76pp, $37 (incl. 2 CDs). |

Helen O'Shea is an Australian fiddler who became aware of and fell in love with Irish music in Canberra in the early 1970s. She got the feeling that Ireland is a mixture of facts and a whole lot of romantic sentimentality, and maybe music is one of the last bastions. Irish music is often said to represent Irishness, and Irish music has been employed in the service of patriotism for quite some time (e.g. Thomas Moore -> FW#37).

The West of Ireland and especially the Willie Clancy Summer School in County Clare (-> FW#36) has become the Mecca or Nashville of traditional Irish music. In an attempt to understand the processes involved in constructing this national musical identity and to investigate the changing dynamics of Irish music, Helen O'Shea follows foreigners playing Irish music at workshops and in pub sessions.

One may note some rather weird attitudes, contrary to public conception. For example, most session musicians in Doolin's pubs are outsiders, are getting paid and the average locals are not interested in traditional music at all. On the other hand, music sessions featuring many locals not always display the Ireland of the Welcomes to the interested foreigner.

Despite claims that each local style reflects the personality of its people and landscape, suggesting an ancient and organic link, distinctive regional styles in Irish traditional music date back only as far as the second half of the nineteenth century. Regional stylistic difference was an effect of musicians' isolation as a result of the significant decrease in population and in movement around Ireland following the Famine of the mid-nineteenth century. The privileging and classification of regional styles (particularly fiddle styles) and their reputation as 'islands of purity' in the increasingly contaminated 'river' of Irish traditional music are much more recent phenomena dating from the post-1950s revival.

The Making of Irish Traditional Music is possibly a rather misleading book title. Helen O'Shea questions concepts of authenticity, where Irishness is claimed as Gaelic, nationalistic and Catholic. She notes the women's absence at the Irish pub session. Traditional music is male-orientated. Session leaders with few exceptions are men, though the majority of learners are female. Is it because traditional music is a bit like rugby? That's what Fintan Vallely observes: you don't watch it, you play it.

Fintan Valelly, Tuned Out: Traditional Music and Identity in Northern Ireland. Cork University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-185918-443-1, 196pp, €39. |

Helen's research is thought-provoking, but in the end it is helpful and healthy, and in no way devaluing the music itself. Even much more precarious perhaps is Fintan Valelly's look at the attitudes of Protestant performers to traditional music in Northern Ireland. In 1993 a bomb was placed in a pub during a traditional music session by a loyalist paramilitary group, warning that venues hosting folk music were considered legitimate targets.

That traditional music is Catholic music, says Fintan, may be popular political pragmatism, but the notion is substantially superficial and uninformed. Traditional music is simply the music that was played all over Irleland by the lower classes, most strongly prior to the invention of recording, cinema, radio and television.

Fintan Valelly, author of "The Blooming Meadows" and editor of "The Companion to Irish Traditional Music" (-> FW#27), is a Catholic who grew up in County Armagh. He began playing the flute in the 1960s and remembers that there were Protestants wholeheartedly involved in music.

I play Irish music because I like it. I wouldnae care if Pope John wrote me a hornpipe, I wouldnae care if Ian Paisley was to write me a jig. I only play the stuff I love.There are far fewer Protestants playing today. The folk revival of the 1950/60s was paralleled by the Troubles, and the issue became thorny and led to a rejection of all things Irish by many Protestants. We in Northern Ireland are not Irish - we do not jig at crossroads, says John Taylor (Ulster Unionist MP). Another popular slogan goes: Catholics dance, Protestants march!

Music is a godly gift. I would relate it to something with a higher power than politics.

I must be the only person ever to have been called a Fenian bastard and a Protestant bastard in the one night - in the same pub, all for playin' traditional music.However, crossroads dances were a feature in many rural areas until the early 20th century - from Kerry in the South West of Ireland to Protestant lowland Scotland. Pipers and harpers moved between Scotland, Wales, England and Ireland since medieval times. Music among Protestant settlers in Northern Ireland was much the same as that already played in Ireland and in Britain.

Only a few examples of the crossing-over of tunes and songs:

the Irish tune "Rakish Paddy" appears in Scottish collections as "Cabar Feigh"; the Scottish "Duke of Atholl's Rant" is the same as the "Humours of Ballyconnell"; there is the same air for two contrasting political songs, the loyal anthem "The Bold Orange Heroes of Comber" and the republican song "Come Out Ye Black and Tans"; "The Sash My Father Wore" is the same as "My Irish Molly O'"; the Jacobite anthem "Mo Ghile Mhear" is the same air as the Protestant origin-myth anthem "Sons of Levi"; airs become political by association, the Irish anthem "Wearin' of the Green" has a Scottish composer, whereas "On the Relief of the City of Derry" has Irish origins; the American Civil War tune "Tramp, the Boys are Marching" became both "God Save Ireland" and "No Pope, Priest or Holy Water"; the Orange marching tune "The Shanghai" is sung in Scotland as a ballad entitled "The Shearin", the same air but with different time signature is the jig/song "Boys of Tandragee" and the reel "The Swallow's Tail".

Tuned Out: Traditional Music and Identity in Northern Ireland is academic but not dreary. Fintan Vallely gives enough background to understand the socio-political situation against which traditional music is observed by Catholics/Separatists and Protestants/Unionists.

John of the Green - the Cheshire Way, or to give it its full Baroque sounding title,

The Famous Triple-Time Hornpipes of North West England, with a Selection of Country

Dance Tunes of the Baroque Era. John Offord has been playing the fiddle for three decades.

After hearing John Kirkpatrick playing some old and rather weird dance tunes from the

North West of England, he fell in love with the stuff and published a collection in the mid 1980s.

This second, expanded edition is a collection of 250 fiddle tunes that were played from the 16th

century until the late 18th century. The introduction didn't make it very clear to me

(there are short German and French introductions too, strangely enough talking about double hornpipes),

it is this: triple hornpipes are dance tunes in 3/2 (or 9/4) time originating from the border areas to Scotland.

These hornpipes are no relatives of the familiar 4/4 tunes of today's Anglo-Celtic music.

They are much more exhilarating, sometimes rather fancy.

Their origin also was an age when (traditional) dance music and Baroque art music

were celebrating a happy marriage, e.g. the suites in Händel's "Water Music" feature 3/2 hornpipes.

The most important part of the book is the collection of tunes, including

staff notation, chords, source details and suggestions about performance.

To mention just a few examples:

The "Lads of Alnwick" survived playing to this day (see e.g. Kerr/Fagan's "Strands of Gold" album);

"Keys of the Cellar" belongs to a family of tunes including

"Bobbing Joan" (e.g. -> FW#24),

and the very well-known "Come Ye O'er fra France" and the "Butterfly" slig jig;

"Cackling of the Hens" is a version of "The Hen's March to the Midden"

(-> FW#36);

the "Foxhunters" hornpipe is essentially the Irish slip jig (-> FW#25);

"Leather Lane" a version of "Carolan's Draught" (-> FW#20);

"New Shields" a version of the "Sailor's Wife" (-> FW#30).

In any case this is great for enlarging the repertoire of any traditional musician.

John Offord included most triple hornpipes he discovered in books and manuscripts until

the mid 1700s, and excluded only those which already appeared in recent Scottish and Northumbrian collections.

John of the Green - the Cheshire Way, or to give it its full Baroque sounding title,

The Famous Triple-Time Hornpipes of North West England, with a Selection of Country

Dance Tunes of the Baroque Era. John Offord has been playing the fiddle for three decades.

After hearing John Kirkpatrick playing some old and rather weird dance tunes from the

North West of England, he fell in love with the stuff and published a collection in the mid 1980s.

This second, expanded edition is a collection of 250 fiddle tunes that were played from the 16th

century until the late 18th century. The introduction didn't make it very clear to me

(there are short German and French introductions too, strangely enough talking about double hornpipes),

it is this: triple hornpipes are dance tunes in 3/2 (or 9/4) time originating from the border areas to Scotland.

These hornpipes are no relatives of the familiar 4/4 tunes of today's Anglo-Celtic music.

They are much more exhilarating, sometimes rather fancy.

Their origin also was an age when (traditional) dance music and Baroque art music

were celebrating a happy marriage, e.g. the suites in Händel's "Water Music" feature 3/2 hornpipes.

The most important part of the book is the collection of tunes, including

staff notation, chords, source details and suggestions about performance.

To mention just a few examples:

The "Lads of Alnwick" survived playing to this day (see e.g. Kerr/Fagan's "Strands of Gold" album);

"Keys of the Cellar" belongs to a family of tunes including

"Bobbing Joan" (e.g. -> FW#24),

and the very well-known "Come Ye O'er fra France" and the "Butterfly" slig jig;

"Cackling of the Hens" is a version of "The Hen's March to the Midden"

(-> FW#36);

the "Foxhunters" hornpipe is essentially the Irish slip jig (-> FW#25);

"Leather Lane" a version of "Carolan's Draught" (-> FW#20);

"New Shields" a version of the "Sailor's Wife" (-> FW#30).

In any case this is great for enlarging the repertoire of any traditional musician.

John Offord included most triple hornpipes he discovered in books and manuscripts until

the mid 1700s, and excluded only those which already appeared in recent Scottish and Northumbrian collections.

John Offord, John of the Green - The Cheshire Way. Green Man Music, 2008, ISBN 978-0-9556324-0-2, 122pp, £15.00 (www.johnofthegreen.co.uk). |

There is no reason why traditional music should not be played exclusively by Protestants in a local, Protestant bar or theatre, as much as by Catholics in a Catholic one. If Italians, French, Germans, Dutch, Swedes, Finns, Jewish-Americans, Scandinavian-Americans, Norwegians, Danes, Bretons, Scots, English and Japanese can do it, so too - if they wish too - can Northern Irish Protestants. And with considerably more connectedness.

There is a great song written by Gary Miller of Whisky Priests fame, reminiscing the life of a Yorkshire man born in 1901. It tells his experiences from coal mining at the height of Britain's prosperity,

Pete Wood, The Elliotts of Birtley. Herron Publishing, 2008, ISBN 978-095406-823-3, 228pp, £15.99 (www.petewood.co.uk). |

Maggie Thatcher christened the striking miners as the enemy within and this could be true for the Elliotts of Birtley in Durham country too. When booked at the Conservative Club during Whitby Folk Week they turned the picture of Thatcher to the wall. Pete Elliott's last instructions: He asked for any limbs and organs to be donated to medical research, if required. However, he requested that his arsehole be sent to the Tory Party.

However, what is here important is not the Elliott family's politics, but rather their place in the 20th century British folk revival. The whole family had been singing all their lifes - at the pub, at home in the kitchen, in the streets playing kids' games. By the time the folk revival came, they realised that pit songs were their own and started collecting. Thus were doing for industrial songs that others, e.g. the Stewarts of Blairgowrie (-> FW#37), did for rural songs.

There's much talk nowadays of the Mersey sound; the Durham sound is another matter. It has more fibre than frenzy, and speaks of real experience in a way that rouses no screams (though some may wince at its force). I invite you to listen to the colliers singing choruses over their beer-mugs. You'd think the place was full of Cossacks. (Bert Lloyd)Peggy Seeger (she wrote a preface) and Ewan MacColl got to know the family during the making of "The Big Hewer", their radio ballad on mining (-> FW#37). They had been desperately looking for pitmen to sing pit songs before, but these always dressed up and sang the hit songs of the day. The programme led on to the Folkways LP "The Elliotts of Birtley" in 1962. In the same year the Elliotts founded the Birtley Folk Club, and run it like you sing around the kitchen.

Pete Wood has been involved in folk music since the early 1960s. In 1974 he moved to the north east of England where he met the Elliotts of Birtley. He fell in love with the family and their club and became determined to write a book about them. It is a study of the family's history, their importance in the folk revival of the 1960s, their strong socialist beliefs, their atheism and their humour ...

... and, of course, their songs. A couple are featured here: Child ballads ("Henry my Son", "Our Goodman" aka "Seven Drunken Nights" -> FW#37), folk songs ("The Banks of the Dee", "Buy Broom Besoms"), mining songs ("Collier's Rant", "Bonnie Pit Laddie"), as well as children's street songs and song games. One striking feature was their sets consisting of fragments of short songs strung together (compare -> FW#36).

There once was the popularity of the black-face minstrel shows in the US: the darkie was allowed to cross borders and express desires ostracised by the Victorian society - from idleness to insobriety.

This continued into the early 20th century under a different disguise. Ragtime burst onto the scene in 1897/98. Its biggest hits were not Scott Joplin's stately piano rags, but coon songs defined ragtime for the masses.

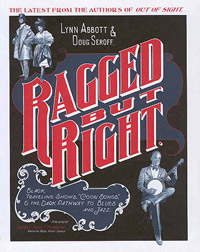

Lynn Abbott & and Doug Seroff, Ragged but Right - Black Traveling Shows, "Coon Songs," and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz. University Press of Mississippi, 2007, ISBN 1-57806-901-7, 461pp, $75.00. |

The 'coon' song, with its ragtime setting, flourishes. There are more of them on the market than ever. In unlimited numbers the people have been turning from symphonies and rhapsodies to such songs as 'Ragtime Life' and 'Goo-Goo Eyes'. Music teachers, in order to make a living, must teach syncopation.Decent people cried havoc about the worst sort of rot, but

I deny the assertion that there is no melody in 'coon' songs. They are light and airy and often full of variety. This low life phase of music which has electrified the world is better performed by degraded southern Negroes than by the best stage artists in existence.

Ragged but Right - Black Traveling Shows, "Coon Songs," and the Dark Pathway to Blues and Jazz is the follow-up to a book called "Out of Sight", covering the years from 1889 to 1895. Drawing from newspapers and entertainment trade papers, Lynn Abbott and Doug Seroff follow black performers, musicians and comedians, their managers, agents and impressarios in vaudeville, circus and minstrel shows. The nice layout of the book reminds of the good old days. There is much detail, maybe too much detail sometimes, including a huge appendix, a song and general index.

The Rabbit's Foot Comedy Company, including a peg-legged dancer, a 268 1/2-pound blues singer with diamonds in her teeth, and a fire eater, was still on the road in the late 1950s. Mary Smith (c.1903-2000), the hefty blues singer with eight diamond inlays, was rediscovered in the late 1970s and became known as Diamond Teeth Mary.

Indeed, coon songs were the primordial soup of the blues. Ma Rainey (later dubbed Mother of the Blues) and Bessie Smith started out as coon shouters. One lyric went: I got the blues, but I'm too damn mean to cry. After 1910 the use of the word coon in popular song diminished, by the middle of the decade the blues sustained the attraction of Afro-American entertainers.

By the dawn of the twentieth century a new style of coon song composition was coming into currency, built around the latest street slang or black colloquialism, which was almost always incorporated in the song title. Many of these specific expressions reverberate in blues and 'old time' country music recordings of the 1920s and 1930s. Popular songs constructed around the latest black slang or vernacular expression were commonplace in rhythm and blues of the 1940s, as well as rock and roll of the 1950s and 1960s. In fact, this characteristic method of composition, a palpable legacy of the coon song era, remains prevalent to the present day.

|

To the German FolkWorld |

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 03/2009

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.