FolkWorld Issue 34 11/2007; Article by Sean Laffey

A Decade of Folk

Songs of the Sea

Irish and Scottish music are on a high, there are thousands of people making excellent traditional music, young children are taking up fiddles and banjos, there is a wealth of opportunities out there to learn tunes from summer schools to the internet. At the recent All Ireland Fleadh this August the world’s biggest session took place, with some 2,700 people sitting down together to play music non-stop for 40 minutes. The future of Celtic music, on all levels, from hobby to profession, seems assured, but what of other musics in the wider British Isles tradition? - Seán Laffey casts a critical eye over the sea song scene.

Years ago, I got a job in a college, I was straight off a degree course myself and thrown in at the deep end teaching maths and science to stroppy teenagers. I had the show down to a fine art, my lessons were over prepared, class notes, diagrams and experiments were arranged with military precision.

|

In November 2006 the international Shanty community celebrated the centenary of the birth of Stan Hugill. This event was to honour his life, work and musical legacy. Who was Stan Hugill? A big question, hard to say because he was many people, we are all social chameleons, but Stan was essentially the self-styled “last shanty man”. He was a wit, raconteur, song collector, author, performer, lecturer and font of knowledge on the culture of the merchant marine in the hey day of sail

Fittingly the tribute took place in Stan’s homeport of Liverpool, the enduring love of the song tradition he inspired was evident when a large number of shanty singers tied up alongside the Marine hotel (at their own expense) to sing for the weekend. The format was simple, Ken and Jan Lardner (the folks behind the Chantey Cabin web site and travelling record store), skillfully pulled the weekend together. They had the show in a cockle shell, Jan put it like this to me “You get a ten minute slot, you can sing or spin yarns but ten minutes is the maximum” The PA system was simple, with enough kit on stage to make the concert work but not too much to extend the breaks between the sets longer than the three songs most musicians chose to sing.

And so it went on for a long weekend, and rarely was there a song repeated, testament in itself to the enormous task Stan Hugill had undertaken in his writings to collate and collect a body of over four hundred shanties and sea songs. A week later and I was back in Ireland, at the desk at the day job, editing stories for Irish Music Magazine. One quote from an interview by John Brophy with the young American Irish pipe player Elliot Grasso struck a chord with me, he said:

“This music has survived for a long while, and there must be something in it of value, which is worth study and preservation. Talking of traditional music, which is handed down orally in many cases and certainly be exposure to a master crafts-person.The chain of musical tradition is long and finely wrought. It is incumbent on each link to maintain its integrity under the pressure brought upon it by the changing conditions around it while remaining unique and distinct from those adjacent.”

Now he was talking specifically about Irish music, but his sentiments apply equally to other folk musics and they fit like a glove into what I assume are the general aspirations of anyone involved in singing folk songs, whether they be Scots Border Ballads, the big songs of South Ulster or sea shanties. We want them to continue, to have a life of their own, to be here when we are not, to be heard above the din of the transient superficial and mediocre music, persist when the pap that is pop is pushed aside for the latest fashion, However, we realize this is a niche music, that it is not an easy art form, it places demands on the singers and their audience, it is at once uniquely personal and intensely communal, by its nature the shanty man has to carry the role in character and the chorus chime in melodically and harmoniously as needs be. We know the genre, we know the repertoire, we know how it is done elsewhere. We’ve seen how well the Bretons have preserved their maritime culture, we know how the Poles have embraced the shanty as a valid form of artistic expression, what we are left with are questions about how well the music is doing in its home ports. That’s a big question and from what I saw at Liverpool, I’m worried.

This isn’t a musical review, I’m not here to sling mud at anyone performance or wrap laurel leaves around the head of the next “Stan Hugill”, there will never be another, we are not talking about the Next Dylan or the Next Christy Moore, when Stan died, so in a way did authenticity, so whatever came next was revivalist in the extreme. Today no one can make their living as a real shanty man, the boats just aren’t there, running a down-easter from Halifax to Boston or shipping Marino wool from Australia to London isn’t done on square riggers, there’s no need for a work song on a container ship shifting steel boxes in and out of Rotterdam. Which leaves the revivalist folk-singer at an artistic cliff edge.

Now let me get back to Liverpool and the weekend in November, and let me share an impression or two with you about the Hugill Centenary. The organisation of the event was exemplary, the venue large and comfortable, the audience respectful and engaged, the singers passionate and committed, everything therefore should have looked rosy, but to my mind there were two ingredients missing, youth and a carrying narrative.

Let me take the latter first. Down a corridor and via a short lift ride to an upper floor, way from the madding crowd in the ballroom, there was a small room with a VCR and TV, and beside those a small collection of tapes of the work of Stan Hugill. I watched the documentaries in the company of Bonnie Milner form New York, singer with the Johnson Girls and a friend of Stan’s.

She found the videos hard to watch, there were so many memories locked away, seeing Stan in his pomp unlocked a deal of sadness at his passing. I watched in awe at his deceptively simple technique, I suppose it is an occupational hazard of mine, but I wasn’t taking too much notice of his singing, but looking for the deeper narrative in his performance. He knew what work went with each song, he could describe the jobs involved, he did so in a physical way, with gestures and semi-mine, saying to us that given the right vessel he could still hoist, haul and clew, in short his narrative added to the perception of authenticity, he took his audience into an archaic and arcane world and back then (in the 1970s) brought along a retinue of fine young singers, those fellows who were now the venerable grey beards singing on stage two floors below me.

She found the videos hard to watch, there were so many memories locked away, seeing Stan in his pomp unlocked a deal of sadness at his passing. I watched in awe at his deceptively simple technique, I suppose it is an occupational hazard of mine, but I wasn’t taking too much notice of his singing, but looking for the deeper narrative in his performance. He knew what work went with each song, he could describe the jobs involved, he did so in a physical way, with gestures and semi-mine, saying to us that given the right vessel he could still hoist, haul and clew, in short his narrative added to the perception of authenticity, he took his audience into an archaic and arcane world and back then (in the 1970s) brought along a retinue of fine young singers, those fellows who were now the venerable grey beards singing on stage two floors below me.

Now I’m not preaching, I’m not without guilt myself, I’ve a little talent, I’ve sung shanties, and I’ve been at it on and off for over thirty years, in colleges, bars and bed rooms, on the decks of a floating museum, in the hold of a trawler, in such exotic harbours as Brest, Le Harve and even New York, but I’ve done next to nothing in the past ten years, and now I’ve knocked on the cabin door of 50, and those five decades are a big wake up call, “get yer sea boots on Johnny and don’t be an idler, the voice and the memory don’t last forever, your chance to inspire the next generation is only a dog watch away from ...”

Then in January 2007 came the news that the maritime song community of Liverpool, would be pushing for a Festival of the Sea for 2008, but their pleas had fallen on deaf ears.

You see Liverpool has a chance to do something really big for folk song, because next year in 2008 the city is the European Capital of Culture (ECC). It is undergoing a major face lift, the old Victorian Sailor town as virtually gone, Stan Hugill often sang “When I was a-walking down Paradise Street“. Today it is a mere two buildings long, not a walk at all. After 2008 the physical legacy of maritime Liverpool will be on the slippery slope to souvenir postcards and artifacts in a dockside museum. But I contend that Liverpool and the folk song community could do something real and timely because it is just what the Shanty Scene needs. Frankly it is a greying cultural movement and needs an injection of younger people if it is to survive beyond the present generation of enthusiasts.

I’d also argue that what we need now is to take a bigger look at folk culture and heritage - beyond shanties - in order to capture a new audience and fire the imagination of a new generation of singers. Perhaps like me you began singing folk in your teens, for me that was when Stan Hugill, Jim McGeehan and Johnny Collins were very much in their prime and some of us stuck at it.

Stan was unique of course, but the others, Louis Killen, Liam Clancy and Ewan MacColl had a special magic about what they did and furthermore how they involved the lore of the sea into their performances, something which was sadly lacking at the recent Hugill Centenary, the scene needs story tellers and yarn spinners, folk song without context and commentary is in a cul-de-sac.

Stan was unique of course, but the others, Louis Killen, Liam Clancy and Ewan MacColl had a special magic about what they did and furthermore how they involved the lore of the sea into their performances, something which was sadly lacking at the recent Hugill Centenary, the scene needs story tellers and yarn spinners, folk song without context and commentary is in a cul-de-sac.

Now the city fathers of Liverpool have run cold water over the idea of a Maritime festival for the City in 2008. Jack Coutts, singer with the world famous Stormalong John, asked me to write a few lines of support in his bid to bring a sea song festival back to Liverpool. What follows now is culled from a longer letter I wrote back in February 2007, to Jack and the powers that be in Liverpool, Jack replied the officials are still silent; you might like to comment on its intentions and feasibility.

I suggested that Liverpool might do something along the lines of a mini-Bristol 96. This in turn was based on the model of the French festival run by Chasse Mareé, and the huge four-yearly Brest Festival Of Maritime Culture. OK it’s copying something from elsewhere, but if the formula is good why not plug in the cash to the equation? Celtic Connections in Glasgow has inspired Celtic Colours in Canada and the Boston ICONS in the USA, so we know that a good idea has legs in the folk world.

My idea to inspire the next generation, was to invite tall ships, have shore side demonstrations, give lectures and hold exhibitions, get schools involved, take the shanties to teenagers and give them a spirit of their own history, walk them around Liverpool’s sailor town, maybe do that soon because I fear there may be only one original building left in Paradise street by the time this year is out. Get other organisations involve, grow a huge snowball from their enthusiasm. Commission theatre, work with local history societies, document what is left of the physical heritage of Maritime Liverpool. Once the physical space has gone it will be hard to fire imaginations in folks who see the cityscape as a collection of Tescos, Woolworths and Dixons.

|

One evening of late as I strolled by the quay Where I met and old shell-back and he told to me Of when he was a young lad and first went to sea And here is the story he told me He said when I was a nipper I joined the Garth Line On a four masted barque I served out my time On a voyage to Australia racing for grain We left these cold shores in the morning Our Captain was Thompson the best you could find A wily old sea dog, ferocious yet kind He'd never shipped steam in the whole of his life For windbags were his only calling And as for the boys who made up the crew A finer young bunch had never worn blue They could sing up a loft with a hullabaloo And every one joined in the chorus We left the brown Humber as the sun its did rise To the girls on the quay we sang our goodbyes And every lad wiped the tears from his eyes As we headed away that cold dawning For over a week the weather was poor Our progress was slow which made us all sore But soon we were rolling as the wind it did roar And we made twelve good knots in the morning We reached Cape Verde on Armistice day And we paid our respects in the usual way And to break the silence we all gathered round As a passenger he took our photos Far off in the distance a steamer we spied And we were o'ertaking her which filled us with pride To think this old lady had such a fine stride and the red duster fluttering behind her But woe to that faulty Admiralty chart For the steamer was fast, her position not marked She was only a hulk, battered and dark And we were all doomed without warning And when the cry came "there's breakers ahead" We knew that her fate and her future was dead Her plates ripped away as she ht the sea bed And her masts and her spars fell asunder The life boat was lowered without much delay And the crew of the Garthpool for the shore pulled away Leaving her sadly to rot and decay As she lay in her grave in the shallows But the songs that we sang on deck and above Were collected by Stan, 'twas a labour of love To honour the sailors who'd got their reward On the barques and the schooners before us And now it's more than a life time ago The last of the windjammers got under tow With a crew of fine fellows all raring to go For to race for the grain that cold morning One evening of late as I passed some time With a salty old shell back, a good friend of mine He told me the story of the last the line And he taught me songs sung aboard her. Sean Laffey 1995 (Tune: Arthur MacBride) |

Record everything you do, every event, every concert, every club night, bring it out as a book and DVD, you might only make one of each to be housed in the Walker Art Gallery, but make and record a positive cultural mark on the year and the city. Form a shanty choir for under 18s and work on it for a year, there should be a TV documentary in it (even if it has to be to pitched at Channel M in rival Manchester). The list of possibilities is endless.

You may have to get the corporate suits involved, but it needs sustained imagination and that drive which made Liverpool one of the great cities of the world and folks with business heads may be just the people you need to get the ball moving. Hosting the ECC is a big event; it will not happen again, think big and go large (as they say in burger king).

Many of those things work here in Ireland, we have some very strong traditional music festivals which champion local music and deep heritage, they take the names of leading players to give a sense of place and a ready access to repertoire, The Willie Clancy Summer School is awash with hundreds of musicians, the William Kennedy piping festival has a truly awe inspiring international dimension, there are many more festivals and they are well funded and well supported.

One of the keystones of those successful Irish festivals is their commitment to the long term, the Willie Clancy Summer School actually auditions its attendees so that they will get the most appropriate experience during the week and sustain the tradition into the future. A Liverpool Maritime Heritage Festival, should in my opinion have a five year plan, be bold in its ambitions, clearly state where it wants to take the music and integrate other aspects of maritime culture as it grows. I’d go for a series of monthly events and a big summer dockside bash, sustain the interest with more events into the closing autumn and winter, make it an integral part of Liverpool culture and not just a weekend of nostalgia.

Ask for a huge tranche of money, have a long list of well thought out projects that require the cash, look to the corporate sector to match it, play the funding game, take advice from organisations like the Association of Festival Organisers, be serious and professional in what you want to do, have a bold vision and paint it onto a huge canvass, in short make Liverpool the Maritime Heritage Capital of the World in 2008.

The sales pitch is easy. It goes without saying that Liverpool has a strong maritime heritage, that its nineteenth century prosperity and its current cultural and physical legacy from those time was due in no small measure to the bold vision of it’s shipping owners and the solidarity of the merchant marine workforce which made Liverpool a world famous centre of commerce, trade and industry.

These attributes should be championed in the twenty first century and I believe that Liverpool has a unique contribution to make not only to European but to World maritime culture and what better year to make such a bold mark than when the city is the cultural showcase of Europe? The qualities that made Liverpool a great city of the nineteenth century, a desire to communicate with the wider world, a spirit of enterprise and noble philanthropy are never out dated, and funding for an imaginative and high profile series of Maritime Cultural events would be money well spent.

I have been involved with folk and traditional music for over 30 years now and have attended, performed and reported on festivals in Great Britain, Ireland, Europe and North America, in my experience when they work they bring an enormous sense of place and civic pride with them.

So to close let me return to my first paragraph, recall that Celtic music is doing very well, it is being played all over the world from Tokyo to Tulla. Why is it so successful?

I have a few ideas, firstly there has been no compromise on musical ability, the Irish Fleadh system and the Scottish Mod both ensure that certain standards are met, you may argue that this can lead to a similarity of styles and a narrowing of repertoire, but the bottom line is teachers and competition players reach an extremely high standard. Young musicians in their mid-teens reach a level of skill to keep them and the tradition in good stead for the rest of their lives. Secondly, there is an undercurrent in Celtic music that sees the culture as being “not of them”, it often manifests itself as Nationalism and indeed this is certainly an extremely important element in the Irish song tradition. This stance, which is contra to the dominant Anglo-American culture, allows for a greater cultural homogeneity in the Irish and Scots traditions. These elements have been missing from the English scene for maybe a generation, chiefly because of a crisis of confidence. To espouse an Anglo-centric view on folk culture could run the risk of musicians being branded as apologist for a colonial-imperialist past and at the extreme as Anglophile racists. Thus in an era where the purse strings controlling cultural trajectories are aimed at fostering multi-culturalism, pluralism and re-visionist history then an Anglo-centric folk song tradition is treated with suspicion to the extent it becomes under-funded and might die out.

I have a few ideas, firstly there has been no compromise on musical ability, the Irish Fleadh system and the Scottish Mod both ensure that certain standards are met, you may argue that this can lead to a similarity of styles and a narrowing of repertoire, but the bottom line is teachers and competition players reach an extremely high standard. Young musicians in their mid-teens reach a level of skill to keep them and the tradition in good stead for the rest of their lives. Secondly, there is an undercurrent in Celtic music that sees the culture as being “not of them”, it often manifests itself as Nationalism and indeed this is certainly an extremely important element in the Irish song tradition. This stance, which is contra to the dominant Anglo-American culture, allows for a greater cultural homogeneity in the Irish and Scots traditions. These elements have been missing from the English scene for maybe a generation, chiefly because of a crisis of confidence. To espouse an Anglo-centric view on folk culture could run the risk of musicians being branded as apologist for a colonial-imperialist past and at the extreme as Anglophile racists. Thus in an era where the purse strings controlling cultural trajectories are aimed at fostering multi-culturalism, pluralism and re-visionist history then an Anglo-centric folk song tradition is treated with suspicion to the extent it becomes under-funded and might die out.

Anyone who knows about the history of the maritime song tradition knows that this was the first cross-over music, English, Irish, American and African musics have all played their role in its development. And that is where the role of narrative is crucial in its current survival; it’s not enough that we sing the old songs we should talk to our audience about them too.

Sean Laffey is Editor of the internationally acclaimed Irish Music Magazine (since 1997), edits the Traditional and Folk Music Directory, and holds the Chicago Watson Award for services to Irish Culture. Is a well-known folk music photographer

(www.redbubble.com/people/tipptoggy) who has had exhibitions in London, Ireland, the USA and Canada. Was a contributor to Keltika Italy and is part of the Mountjoy writers group in Illinois. He holds a Masters Degree from the University of Exeter.

Sean Laffey is Editor of the internationally acclaimed Irish Music Magazine (since 1997), edits the Traditional and Folk Music Directory, and holds the Chicago Watson Award for services to Irish Culture. Is a well-known folk music photographer

(www.redbubble.com/people/tipptoggy) who has had exhibitions in London, Ireland, the USA and Canada. Was a contributor to Keltika Italy and is part of the Mountjoy writers group in Illinois. He holds a Masters Degree from the University of Exeter.

He is a shanty singer and has performed at international maritime festivals in Paimpol, Brest, Douarnenez, Le Harve , Hull and Bristol. He has performed in New York and has recorded albums with Jenkins Ear, Warp Four and Liam Clancy. He has written two folk performance documentaries on maritime culture - “Wooden Ships and Iron Men” and “George and Stan the Last Windjammer Boys,” the true story of Liverpool’s Stan Hugill and the ill feted Garthpool. He is currently chair of the Cashel St. Patrick’s Day Parade and the Cashel International Celtic Festival. In the past he ran the Cashel Summer Festival - always on time and on budget. He is the Treasurer of the Cashel Chamber of Trade and Tourism. He was a team member who developed www.cashel.ie, a web site for the world heritage site of the Rock of Cashel. When not working on folk and traditional culture he teaches children with special needs. He sang his own composition, “The Last Windjammer Boy” which tells of Stan Hugill’s adventure on the last commercial sailing ship, the Garthpool. For more on the campaign to get a shanty festival in Liverpool please visit shantiesinliverpool.blogspot.com. |

Photo Credits:

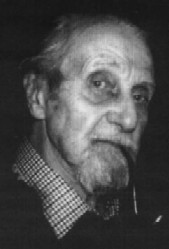

(1), (5) Stan Hugill (from website);

(2) Mike O'Leary,

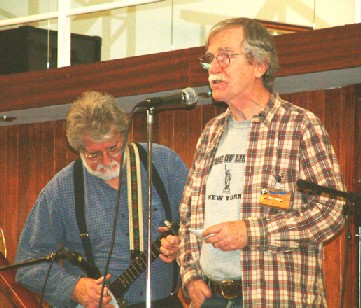

(3) Bob Conroy & Dan Milner,

(4) Jim McGeehan & Johnny Collins

(by Sean Laffey, Stan Hugill Centenary, Liverpool November 2006).

|

To the German FolkWorld |

© The Mollis - Editors of FolkWorld; Published 11/2007

All material published in FolkWorld is © The Author via FolkWorld. Storage for private use is allowed and welcome. Reviews and extracts of up to 200 words may be freely quoted and reproduced, if source and author are acknowledged. For any other reproduction please ask the Editors for permission. Although any external links from FolkWorld are chosen with greatest care, FolkWorld and its editors do not take any responsibility for the content of the linked external websites.